Kirk Schleiffarth is currently a Ph.D. candidate at Northern Arizona University (2014-present). He has experience studying a variety of volcano-tectonic provinces with a variety of techniques. In 2010, he spent several months monitoring and cataloging volcanic activity at Colima volcano in Mexico. From 2012-2014, he investigated the Eocene Challis Volcanic Field in central Idaho for his master’s degree using geochemistry and geologic mapping. In 2017, Kirk spent 2 months in New Zealand comparing hyperspectral and geochemical results from the Tongariro volcanic complex for a volcano hazards project. He currently works on understanding the tectonic significance of volcanoes in Central Anatolia (Turkey) using geochronology, igneous geochemistry, and structural geology. Kirk is an executive committee member of TravelingGeologist.com.

Volcano Questions

I was half asleep in my tent on the slopes of Colima volcano in Mexico after a long day of monitoring its activity. I purposely left the tent cover off in order to keep cool but more importantly, so I could keep an eye on the volcano in case it erupted during the night. Around 3 a.m., the volcano came to life; with a sudden and thunderous roar, it spewed ash into the sky and triggered an avalanche of glowing, hot rocks down its slopes directly towards me. I excitedly yelled at the other scientist I was working with and scurried toward the monitoring equipment to make sure we were collecting the data we needed. Once we checked that the equipment was working, we watched the volcanic event unfold, snapping photos of the impressive display. The eruption was a relatively brief episode, and within 10 minutes all was quiet. The thrill of observing even just a small part of the volcanic process was enough to keep me up for the rest of the night. I began to think: Why did this volcano form here? Why did it erupt now? When would it erupt again?

Who Cares?

These questions drive me to research volcanoes all over the world. One of the major themes of my research has been the quest to understand why volcanoes are located where they are. What controls where they form? Why do they form in some places and not others? Ultimately, this matters because volcanoes are dangerous and variable. They can have devastating effects on property, landscapes, ecosystems, local and international economies, climate, and human life. My Ph.D. research is on volcanoes in Turkey because little is known about why they formed there and how they are related to the regional plate tectonics. To study these poorly known volcanoes, I sought to collect rock samples from the slopes of more than 20 volcanoes in central Turkey, hoping they would provide information on how the magma formed, how deep it formed, and when it erupted to create these interesting volcanoes.

Looking towards Erciyes volcano, the largest of the region, from the north. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork is often the highlight of the research process for geologists; and that certainly was the case for me in remote, central Turkey. After a year of prep work, including reading scientific literature, pouring over geologic maps, and studying the region on Google Earth from every angle possible, actually being there felt a little unreal and overwhelming. I quickly learned that fieldwork in Turkey is different than fieldwork in the western U.S.A. and in some ways, much more luxurious. Instead of camping, we stayed in hotels. Instead of hiking long distances, we drove a rental car. Instead of fearing bears or rattlesnakes, I feared the Kangal shepherd dogs. Some of these differences were a product of the nature of my work; I had to cover more than 500 km and collect samples from each volcano along the way! However, some of these differences were unique to Turkey just like the volcanoes I came to study.

Fear of the Kangal Dog

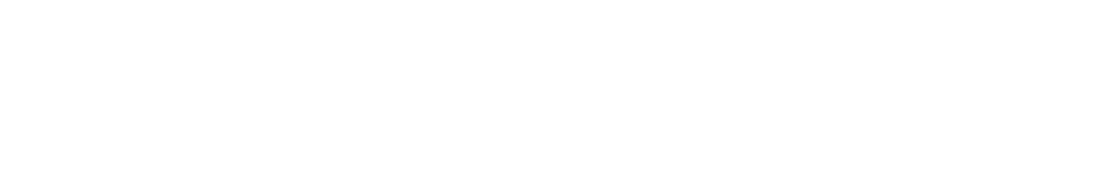

Early on during my first field season, I collaborated with proto Dr. Mike Darin for a couple of days on an older, eroded volcano that we thought might represent the oldest in the region. We marked a waypoint where we wanted to collect a rock sample, and watched our GPS device carefully as we drove up a bumpy, gravel road. We took the road as high as we could to a small saddle in the topography. The rocks we wanted were up on the mountain to our left, along with a flock of sheep and their K9 shepherd. We both sunk our heads in frustration, knowing that we shouldn’t approach a flock of sheep protected by a Kangal dog – they are known to be overly protective and aggressive. I asked myself if I really cared about this sample that much. After some discussion, Mike and I decided that we needed the sample but had to move quickly and quietly to not get the attention of the dogs. We hiked silently up the mountain through tall grass, hunched over to avoid being seen. I suddenly felt less like a geologist seeking samples and more like a soldier going into combat. The only thing I had to defend myself however, was a rock hammer and a tiny hand lens used to break open and look at rocks up close – a common accessory for most geologists. Fortunately, I only had to use my geology tools for their intended tasks. We collected a sample and returned to the car unnoticed and unscathed with a new, very important sample.

Layers of volcanic rocks are cross-cut by a mafic dike – well exposed in a road cut. Photo by Mike Darin.

A scenic view of remote Central Turkey where old volcanoes have eroded into various small mountaind and hills. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

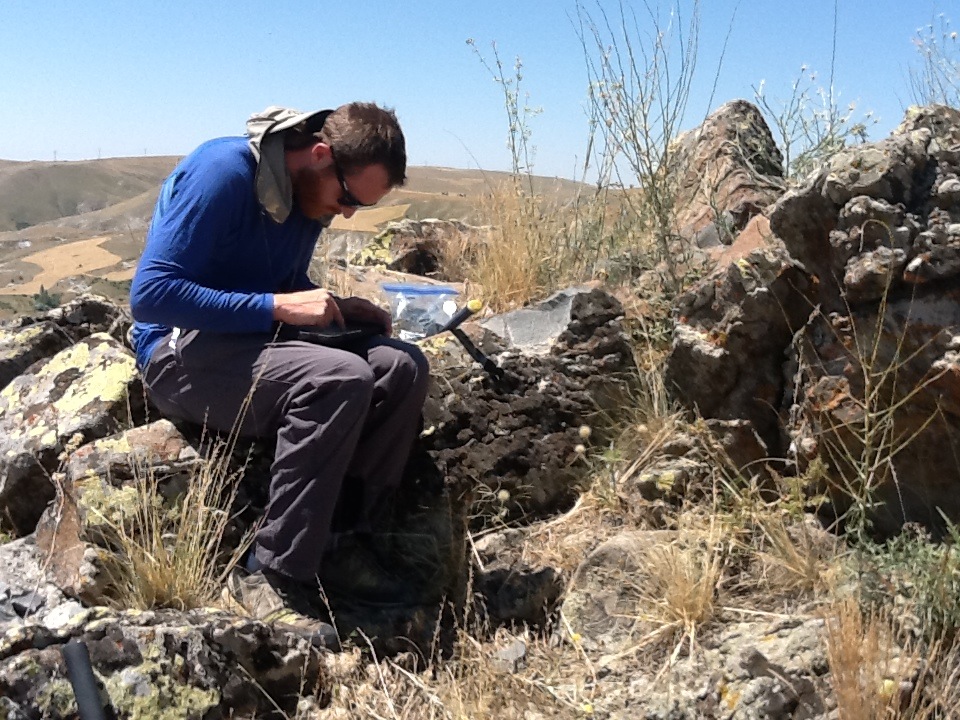

New Hypothesis

I collected many other samples over the following months and I slowly became more familiar with the various volcanoes in central Turkey. That summer’s fieldwork yielded great initial results, which helped me develop a new hypothesis that I was eager to test. My theory was that the volcanoes of central Turkey were getting younger to the southwest towards the Mediterranean Sea; an idea that had not been suggested before. If this is true, it will have significant implications for understanding why volcanoes are present in central Turkey and where they might erupt again. The following summer, I returned eager to test my hypothesis. I knew the towns, I knew the roads, I knew about 10 words in Turkish, I knew to stay away from sheep, and most importantly, I knew the volcanoes. With my enthusiastic Turkish field assistant(s), we scoured the countryside, collecting over 100 samples from more than 20 different volcanoes from an area greater than 15,000 km2. We were hoping to get isotopic ages that would prove my hypothesis correct and systematically worked our way towards the southwest.

Curious Farmer

Several of the volcanoes that we collected samples from were now discreet, eroded, and unassuming hills, making it difficult for locals to recognize or appreciate the interesting geology around them. We had become accustomed to explaining our work to suspicious locals, jumping fences, and navigating bad roads, which is exactly what we had to do to collect a sample from Hoduldag volcano. This volcano rises above beautiful grassland and is in one of the more difficult-to-access and remote regions of the field area. After a heinous drive, jumping a fence, and collecting the samples we needed, we started the hike back to the car. It was parked on the side of a gravel road near what seemed to be an abandoned farmhouse. As we got closer, we noticed a man emerge from the small building. From over a hundred meters away, he began yelling and asking in Turkish, ‘What are you doing here? This is my land, what are you doing here?’ My field assistant told him we are geologists but the man insisted we come to him. It seemed he needed a better explanation.

We spent the following several hours with this curious farmer in his humble home, sharing stories while he insisted we drink his tea and eat his fresh mushrooms. He abstained from eating because he was observing Ramadan. Despite living in a very small home with no electricity, this man was eager to share everything he had with us and was extremely curious about our work and the rocks beneath his land. We briefly told the farmer that the mountain in his backyard was an old volcano, one of many that covered the countryside and erupted frequently not so long ago, geologically speaking.

Ramadan dinner. One perk to doing fieldwork during Ramadan – feasts at night once everyone stops fasting. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

The Aladag mountains, part of the Central Taurus mountain range in south-central Turkey. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Wrap-Up

The volcanoes of central Turkey have a range of ages between ~12 and 0 million years old and appear to decrease in age towards the southwest near the Mediterranean Sea. In general, my hypothesis was proven correct but it’s always a little more complicated than it might appear. These results show that yes, there is a regional southwestern pattern of where and when the volcanoes first erupt, but there is some variability at a smaller scale. I think the volcanoes of central Turkey generally formed above a southwestward migrating deep mantle source (or in geology terms – flat subduction in the Oligocene and early Miocene eventually led to southwestward slab rollback and magmatism). I attribute the irregularity in the pattern to many factors mostly related to variability of deep rocks and faults through which the magma had to rise. Although my fieldwork was completed that summer, I am still in the process of analyzing other data and thinking about why those volcanoes formed where they did and what the observed age pattern actually means. Often figuring out the explanation of geologic observations begins with identifying regions on Earth with similar patterns controlled by known processes. Similar volcanic patterns of decreasing age towards the continental margin is seen in many places (e.g., western U.S.A., central Mexico, Italy, New Zealand, etc.) but Turkey remains unique and interesting, much like the field experiences I had. I look forward to studying more volcanoes and the all experiences that come with it.

Organizing and labeling rock samples before shipment to various laboratories. Photo by Jamie Can Brown.

All work funded by NSF Award Abstract #1109826

COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH: Central Anatolian Tectonics (CD-CAT): Surface to mantle dynamics during collision to escape https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1109826&HistoricalAwards=false

Further Reading:

Scientific publication

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315977631_Shallow_melting_of_MORB-like_mantle_under_hot_continental_lithosphere_Central_Anatolia

Non-technical description of multidisciplinary project

https://www.esci.umn.edu/groups/CD-CAT/CD-CAT-101-Non-Technical-Description

Extra Photos:

This natural rock formation made of volcanic ash flow deposits was carved into to create Uchisar (tip-top castle), an ancient fortress in the region. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Overlooking the ash flow deposits (ignimbrites) of Cappadocia from Uchisar Castle. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Looking at an ignimbrite in Cappadocia. These deposits are formed by explosive eruptions and ground-hugging ash flows, creating a variety of layers and cross-beds. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Inside the underground city of Kaymakli in Cappadocia. This city was carved into the soft volcanic rock by the Phrygians, an Indo-European people, in the 8th–7th centuries B.C. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Natural erosion by rain water formed this tight canyon within the ignimbrites of Cappadocia. Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Volcanic bomb likely landed in soft, unconsolidated volcanic tephra forming a “bomb-sag.” Photo by Kirk Schleiffarth.

Old pillow lava flows, formed by erupting into water, are variably eroding and somewhat obscured by clay and younger soils. Photo by Mike Darin.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.