Caden J Howlett is a field geologist with a broad interest in understanding the long-term behavior of the lithosphere. He is passionate about thrust belts, core complexes, and science communication. See Caden’s YouTube for videos on a variety of topics ranging from Andes fieldwork to graduate school advice (www.youtube.com/c/CadenHowlett).

Cerro Mercedario is the eighth-highest mountain in the Andes at 6720m asl (22,047ft). My field partner Chance Ronemus and I worked the first three weeks of our 2022 field season in the Manantiales Basin, directly east of the mountain. Every late afternoon while measuring section, Mercedario’s enormous triangular shadow would bury us. A mountain inspiring and high with an uplift history so intimately linked to the adjacent basin record—we knew we had to try climbing it.

On a mountain like Mercedario, you need good vibes and good weather. The latter had proven to be much less consistent. Every time we were in service in the adjacent and adored Barreal, we would look at weather models for the summit. I’d open the models and see a forecast something like this:

Temp (F): High-2, Low- -10

Wind (mph): Sustained-40, Gusting-80

“Cold temperatures and sustained dangerous winds. Snowfall overnight.”

I’d just pocket my phone and tell myself that those numbers are a problem for future us. While we were measuring section in Manantiales relatively low and comfy and well-fed, there was a five-day period where Mercedario was completed buried in towering cumulonimbus. When they broke, the summit was covered in snow, I’d guess half a meter. After completing the first phase of a major field objective in Manantiales, we went into Barreal for a resupply. We checked the forecast, and it looked like a few days of questionable weather followed by a more promising window of consecutive clear days. We decided to spend two days in a nearby range called the Cordillera Del Tigre sampling for thermochronology and then go back to Barreal for a forecast. On our way back to Barreal after those two days, we knew it was time to “fish or cut bait” as our friend Pete DeCelles would say. The forecast looked mostly good with a few questionable days in the middle with high-ish winds and evening snow showers. But we felt comfortable, so we decided the spend the whole morning prepping gear and food and would head into the region that evening.

We resupplied food in Barreal – gathering what we could. Main supply: 20 bags of instant mashed potatoes. Secondary supplies: rice, ketchup, Yerba mate, hard candies, some cans of tuna. We had other calories to supplement, but we knew it would be a pretty low-calorie expedition haha.

We set out all our food on a park bench and repackaged everything so it was as light as possible and to save on trash we would otherwise have to pack out. While in the park, two people came up to us and asked what we were doing. One of the guys ended up giving us a paper bag full of baked treats, danish-like. Homieee. We binned our food, got diesel, and drove southwest out of Barreal towards the La Ramada Massif.

You can see the summit of Mercedario and the surrounding mountains on the drive in—so we were driving at 1900m above sea level looking directly at our 6700 m goal in the distance. We punched the truck through some rivers and through a huge gorge that represents the eastern front of the high Andes. The well-established gravel road (thanks to a mining operation to the north) took us to the starting point for our intended route up Mercedario, a place called Laguna Blanca at 3300 m asl. There were a few scattered vehicles, a small, smoke-blackened concrete hut, and a gaucho with a few thin horses. We set up our tent and made spaghetti with salami and spinach, our last decent meal we would have for a little while. Before bed we walked around and got a little perspective on the river that went through our camp. All the water in the river is sourced from the glaciers on the southwest side of Mercedario, so it was cool to already feel somewhat attached to the mountain.

The convergence of tectonic plates causes rocks to bend, break, pile up, and rise to high elevations. As mountains like the Andes of South America rise, they get worn down by rain, wind, ice, and gravity. Geologists can analyze elements in rocks to determine when erosion happened, which tells us when mountains were growing. Sampling at high elevation is a powerful approach because the highest rocks usually reach Earth’s surface first, recording the earliest phases of mountain building. This approach known as thermochronology broken down in its Greek roots is “the study of heat and time.” In a geological context, it refers to the study of the thermal history of rocks and minerals.

No hurry the following day. We loaded moderately heavy packs with all the gear and food, probably 26-28kg each. It was a short hike from the truck to basecamp, also known as Guanaquito. Maybe 4 km with 500m of gain. We set up camp at Guanaquito and jaunted up to the southwest to get used to altitude and get a view of the Cabillito Glacier on the east side of Mercedario. The mountain itself was buried in dark gray clouds that dramatically peeled away over the course of an hour. We never saw the summit but knew that it was back there. We walked back to camp and had dinner (tuna, risotto, and a hard candy).

Our camp was surrounded by guanacos, llamas that live in the high Andes. They are mostly chill animals that spend most their time grazing; but once a day, you will hear one let out a blood curdling scream and run at full speed across talus fields. Shocking.

After our first night at base camp, we did a gear carry to Camp 1 (Cuesta Blanca). For the uninitiated, this is where you carry some of your gear up to a higher elevation camp and bury/stash it for the following day. It allows you to acclimate, see the route between camps, and reduce your load for the push up. About 200m above our base camp we came across a German man called Conrad. He was looking rough—he had spent the last 10 days on the mountain. He had spent two nights at camp two (Pirca de Indios) at 5100m (17,000ft) in a big windstorm. He told us he didn’t attempt the summit because he had the flu and had left his partner up at the high camp because he wanted to try the summit again. We learned his partner’s name was Wolfgang and told Conrad we would keep an eye out for him. We pushed up along a beautiful stream that alternated above and below ground. The gear carry from Guanaquito to Cuesta Blanca gained about 800m and we buried our gear under rockfall at 4350m. Because we were going back down to base camp, it made sense to grab a rock sample and get it as low as possible for the hike out. So, we carried our sample from Cuesta Blanca back down to base camp. The first sample of the mission was a good feeling.

The following day we pushed our camp up to Cuesta Blanca and set up our tent at 4300m. Chance and I built a pirca (rock wall) surrounding our tent to protect it from the wind and recounted our calories, about 1200 calories each per day. Not very much considering the elevation and the climbs between camps. It definitely wasn’t enough to loiter around camps if the weather turned. We each took our first Diamox and slept 12 hours.

Chance and I woke up the next morning to hail and snow with some minor winds. We were inside of a cloud, always a cool feeling. We had planned to spend the whole day at Cuesta Blanca as a rest day to acclimate. With the weather hitting us, it was clear that we would be sitting in the tent all day. One major mistake we made: no books and no cards! We had almost nothing to kill time at camp. Fortunately, Chance had a few books downloaded on Audible. So we spent the next 12 hours drinking mate and listening to Ted Chiang short stories. We also started the audiobook Cixin Liu’s The Three Body Problem—a book I recommend, followed by the rest of the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy. We ate a Ramen bomb—two panels of Ramen with a double mashed potato added. Yummy salt. A few times during the day I could see a hole through the clouds to a clean blue sky. Thin air. It would last a minute and we would be consumed by the cloud again. At one point we were filling water and two men walked out of the cloud. We said hello and they approached us. It was Conrad and the legendary Wolfgang! Conrad had come up to grab his pack he abandoned days earlier; apparently, he’d gotten over the flu. Wolfgang, a sixty-something year old German man, had spent three nights at the higher camp above and failed at two summit attempts. He was a sight to behold with a towering ancient backpack. Chance and I still laugh about the fact that he had at least three huge thermoses attached to his pack. Not cutting any weight. I swear to God he told us that he had to turn around 50m below the summit. We talked for a while and said goodbye.

We decided to skip a gear carry to the next camp (Pirca de Indios) the following day. The combination of feeling healthy and how few calories we had inspired us to just push up with all our stuff and take another rest day up high. Pirca camp is at ~5100m and is probably where climbers begin to feel the elevation.

The move from Cuesta Blanca to Pirca was beautiful. Chance said that it was the first time it felt like we were getting high, and I agreed. A steep cirque head wall above Cuesta Blanca rolled into a relatively flat, high-elevation drainage between 4750 and 5000m. For the first time, the large glaciers that scrape the high flanks of the mountain came into view. A view to the east over dozens of 5km high peaks was wonderful. The primary rock type in this region—known as the Choiyoi Group—is a sea of variably textured and colored igneous rocks. Granites, ignimbrites and rhyolites dominate the landscape, with gradational pastels from pink to orange to white. Another steep cirque head wall was encountered for the last 300m of gain up to Pirca camp. This wall rolled into a tight little cirque with a large glacier pressed against its northwest side. The glacier shares the same name as the camp (Pirca de Indios).

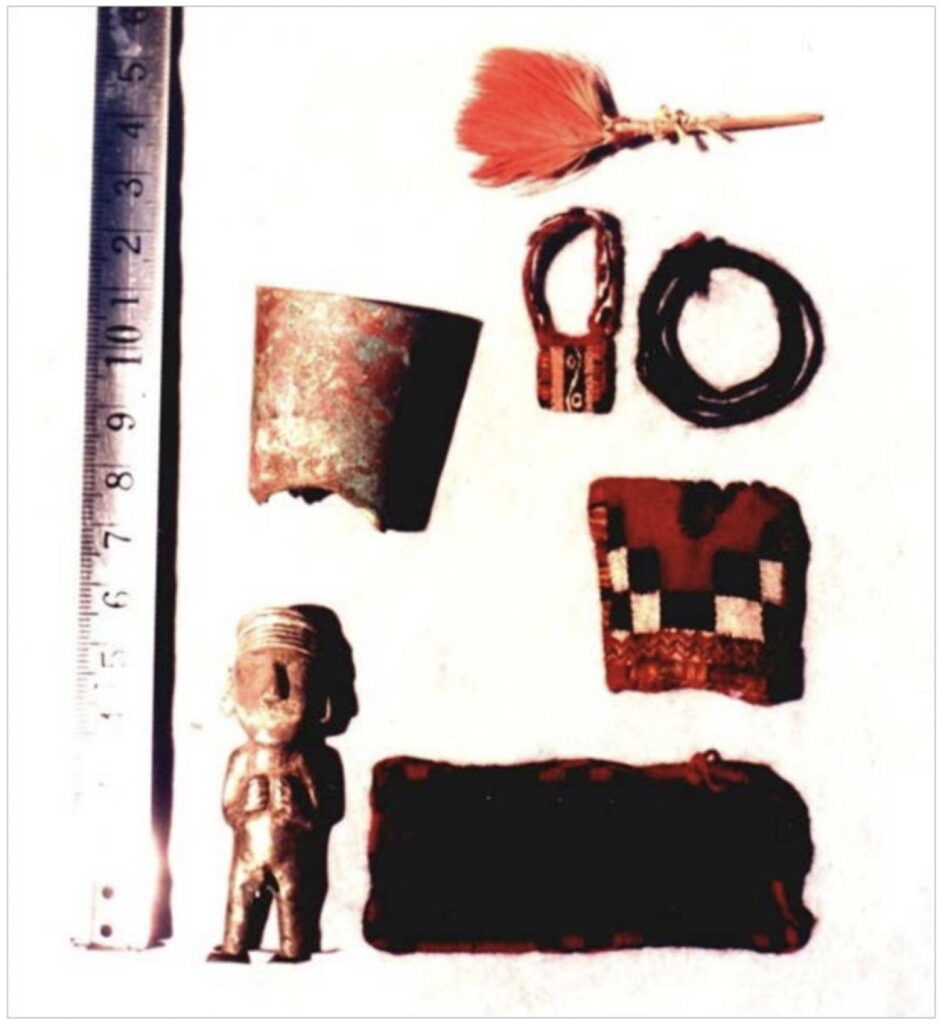

The Polish, Italians, and Japanese are celebrated for various first ascents on Mercedario, but it had been summitted centuries earlier. The name Pirca de Indios comes from the discovery of Incan alter ruins and small statues honoring the Inti (Dios del Sol; or “Sun God”) on the highest flanks of Mercedario. Archeologists think that the first ascent of Mercedario was accomplished by the Incans (approximately 500 years ago) based on the proximity of these ruins to the summit. Artifacts have been found between 6000 and 6200 meters that are consistent with capacocha, a significant sacrificial ritual in the Inca Empire that involved the sacrifice of children and young women to the empire’s most important deities. The most famous example of this practice is the “Children of Llullaillaco”, three almost perfectly preserved Incan children found on a 6700 m summit in NW Argentina (Reinhard & Ceruti, 2010). A rich history and literature surround high-altitude archaeology along strike of the high Andes and I direct you towards the work of Dr. Constanza Ceruti at Universidad Católica de Salta for a starting point.

We set our packs down in a suitable location for camp and walked to the glacier to fill our 4L water bladder and four Nalgenes. What a special feeling it is to simply place your bottle beneath a crystal-clear stream of glacier melt. You could see through the frigid water right into the blue ice of the glacier.

We sat around camp, hydrated, and eventually ate a “risotto bomb”— you guessed it: risotto with double mashed potatoes. A hard candy for dessert. As soon as the sun went behind the cirque headwall, the temperature plummeted. We took some Diamox, which helped a ton to reduce our resting heart rate. A light wind against the tent put me to sleep. Overall, we slept great. Each time I woke up to progressively zip up my sleeping bag, I heard the most interesting noise. It was a loud banging sound that echoed across the cirque. It sounded like someone throwing a bag of concrete mix into the bed of an old truck. By 3 or 4am, I had to get out to pee. I put on some down layers and got out of my bag. As I unzipped the tent, I felt the freezing air against my face. I got out and zipped the tent up behind me (Chance’s good tent held a lot of body heat inside; RIP to that wonderful tent, which was shredded and blew away during a biblical windstorm weeks later). I turned around to one of the better nights skies I have ever seen. A new moon at elevation with no cloud cover. The plane of the Milky Way like someone had ripped open the sky. Brilliant. Constellations were almost impossible to make out due to the density of the stars. Orion (an Austral summer constellation) was discernable, mostly thanks to the red giant Betelgeuse (Orion’s shoulder). Orion is upside down in the southern hemisphere – cool. As I stood in awe, I heard the loud bang once again. BLAAAP! Outside, I could tell where it was coming from: glacier Pirca de Indios. The noise I had heard through the night was glacier cracking, I should’ve known. It was an amazing experience of my life. I got back in the tent and slept on and off until 8AM.

My Nalgene was partially frozen in the tent that morning. I was thinking how tough it would be to motivate ourselves on summit attempt morning, when we would be up before the sun. Once the sun did hit, we made mate and coffee. I had a cup of granola and sucked on a frozen piece of Nutella. We probably got out of the tent around 9:30am. With no gear carry between Cuesta and Pirca, we had to do a rest day at Pirca to acclimate. The only thing on the agenda was to climb 500m above our camp to sample a glistening white granite for thermochronology. This would be our third highest sample, with one planned at 6000m and another at the summit (6720m). My resting heart rate was normal and my O2 sat was 93%. Chance was good too.

Before sampling, I went to the glacier to refill water. There was almost no water coming off the glacier, much different than the torrent coming off the previous afternoon. Cold, frozen. I thought about the intimate moment I shared with the glacier the previous night and its daily cycle deeper into the brittle regime. During our rest day, we sampled the granite, listened to The Three Body Problem, ate a ramen, and drank water. A good day. We planned to skip the normal high camp the following day. We are in fine shape so we figured it would be riskier (or at least shittier) to sleep at 6000m than it would be to push a 1800m summit day.

We went to sleep around 8pm, with our alarms set for 430am. This is a pretty late start for the size of the day, but we did not want to spend too much time in single digit temps. The glacier cracked all through the night again. The alarm didn’t wake me up…the wind did. At around 3am it started whipping. The highest winds of the whole trip to that point. Of course. We started moving around the tent at 430 or so, making mate and coffee. I’ll never forget listening to “Dance Crip” by Trueno while our red headlamp lights interacted with steam coming off our mate. Nutella cube. I put on all my layers. We strapped up our mountain boots and got out into the dark. The coldest time of the entire day. Truthfully, it could have been much worse. The winds were manageable, and our gear was adequate for staying warm, especially once we started moving. We started up the headwall, about 350m of gain in 800m of distance. By the time I was at 5700m, the rising sunlight hit me on the ridge. I felt it in my bones. An incredible sight to see the sunrise over the expansive central Andes to the north. Chance and I mostly pushed without talking until we reached the high camp. The elevation was felt, but we were off to a good start.

Cerro Mercedario is a huge pyramid. The route takes you up the northeastern ridge of the mountain, steep and moderately exposed. We could see half of the summit ridge from the high camp—it was clear we had a long journey ahead. We had some Lays potato chips and continued up. After two or three hours, we reached the final part of the climb. The final mile or so takes you up from 6200 to ~6700m. It is a long, straight shot across a large field of talus, snow, and ice. We did little talking and kept a consistent slow pace. It took several hours to cross this section. We stopped once and melted snow in our stove for a liter of water each.

The hardest part of the climb was the final 800m to the summit. The summit seemed so high above us still. For much of the last hour, I was counting off my steps. Chance and I took turns leading. I remember Chance saying between steps, “buddy, it looks like we are about to run out of mountain.” We wrapped up around the northwest side of the summit onto a small ledge. I could see a small piece of rebar with a little blue flag 30m up. We pushed up together and before I even looked around I gave Chance a huge hug. We hollered. It was a satisfying summit with my best buddy.

The view from the summit was amazing. Looking east, we could see over the eastern front of the High Andes into the portion of the thrust belt known as the Precordillera. Past that, flat land interrupted by the occasional Sierras Pampeanas uplift. Central Argentina, the geological equivalent of the Great Plains of North America. To the north, the central Andes as far as the eye could see. Several other 6000m peaks shot out of the ground, smothered by glaciers. To the west, the Principal Cordillera. Huge walls of maroon and white sedimentary rocks that are folded and repeated over themselves. Beyond Chile, the Pacific Ocean. Approximately 50 km south, Aconcagua. One of the seven summits and the largest mountain outside of Asia (Aconcagua is 6969m, about 200m higher than Mercedario).

We spent about a half hour on the summit and sampled for thermochronology. We took some pictures and started down at around 2pm. A summit with great weather. We sampled again at ~6020m and made it back to Pirca at 5pm. Neither of us wanted to sleep a third night at Pirca, so we made the bold (?) decision to push all the way down to Cuesta Blanca. We drank from the glacier and romped down to Cuesta, arriving around 7pm. In total, the day was 1700m (~5600ft) gain from Pirca to summit, and then 2600m (~8600ft) descent from summit to Cuesta. A heroic effort haha. The 12kg of rock in my pack on top of all my gear was a test of my strength. We ate mashed potatoes and a candy at Cuesta, basically out of food at this point. I made a chamomile tea that I had saved the entire trip—it was amazing.

We slept for 10 or 11 hours and left Cuesta after coffee and mate. We picked up gear (and another rock sample) we had stashed at the Guanaquito basecamp. At this point, our packs were HEAVY with rock and gear. But we were back in the land of life, with tough green vegetation hugging the banks of gurgling streams, birds, and guanacos galloping around. We made it back to the truck at about 1pm. We didn’t have much food at the truck, but we had cerveza. Chance and I sprayed beer around in celebration and drank a few pints. We unloaded our rock samples and made sure our notes were coherent. In total, we had seven samples spanning a pseudo-vertical profile with 4.4 km of relief.

We drove 2 hours out to Barreal and went to Don Lisandro’s house. We had an epic multi-course meal with a bottle of Malbec. It was a great end to a successful mission.

Looking back on my notes, there were times that I felt tired and uneasy. One of my potentially hypoxic notes from Pirca camp: “I’m not sure if we feel good or bad about our chances and I think that is why we like it.” It gives you an appreciation for life and the power of nature. Going to these places apparently suitable for making sacrifices to the gods. Like most geologists, I will forever be humbled by mountain belts and nature. Thanks to Cerro Mercedario for allowing us to scale it safely and return home.

The results from this expedition were recently published in Tectonics (Howlett et al., 2025; doi.org/10.1029/2024TC008433). We went back to the eastern flank of Mercedario for a few weeks the year after summitting and did some mapping. Our thermochronology and mapping efforts integrated with thermal history modeling and a regional synthesis of deformation shed some light on the timing of shortening in this region. In combination with a companion study led by Chance in the Manantiales basin (Ronemus et al., 2024; doi.org/10.1029/2023TC008100), we hope our work provides some thought-provoking ideas on orogenic wedge behavior and the evolution of the south-central Andes.

We are grateful to our friends at CONICET-IANIGLA in Mendoza for insightful discussions and logistical assistance. Valuable previous work in the region helped direct our research efforts, including but not limited to Alvarez et al. (1995); Alvarez & Ramos (1999); Cristillini & Ramos (2000); Mazzitelli (2020); Ramos et al. (1996); Hoke et al. (2015); Jordan et al. (1996); Lossada et al. (2017, 2020); Perez (1995); Mackaman-Lofland et al. (2020); and Suriano et al., (2017).

Chance is thanked for reading an early version of this trip report. Our PhD advisors, Pete DeCelles and Barbara Carrapa, are acknowledged for their long history fusing climbing and exploration with exceptional field science. They inspired the mission.

References:

Alvarez, P. P., Benoit, S. V., Ottone, E. G. (1995). Las Formaciones Rancho de Lata, Los Patillos y otras unidades Mesozoicas de la Cordillera Principal de San Juan. Revista de la Asociacion Geologica Argentina, 49 (1-2), 133-52.

Alvarez, P. P., & Ramos, V. A. (1999). The Mercedario rift system in the principal Cordillera of Argentina and Chile (32° SL). Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 12(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-9811(99)00004-8

Cristallini, E. O., & Ramos, V. A. (2000). Thick-skinned and thin-skinned thrusting in the La Ramada fold and thrust belt: crustal evolution of the High Andes of San Juan, Argentina (32°SL). Tectonophysics, 317(3–4), 205–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1951(99)00276-0

Hoke, G. D., Graber, N. R., Mescua, J. F., Giambiagi, L. B., Fitzgerald, P. G., & Metcalf, J. R. (2015). Near pure surface uplift of the Argentine Frontal Cordillera: insights from (U–Th)/He thermochronometry and geomorphic analysis. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 399(1), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP399.4

Howlett, C.J., Ronemus, C.B., Carrapa, B., DeCelles, P.G. (2025). Miocene construction of the High Andes recorded by exhumation of the Frontal Cordillera, La Ramada Massif of western Argentina (32°S), Tectonics, 44, e2024TC008433. doi:10.1029/2024TC008433.

Jordan, T. E., Tamm, V., Figueroa, G., Flemings, P. B., Richards, D., Tabbutt, K., & Cheatham, T. (1996). Development of the Miocene Manantiales foreland basin , Principal Cordillera, San Juan, Argentina. Andean Geology, 23(1), 43–79.

Lossada, A. C., Giambiagi, L., Hoke, G. D., Fitzgerald, P. G., Creixell, C., Murillo, I., et al. (2017). Thermochronologic Evidence for Late Eocene Andean Mountain Building at 30°S: Eocene Andean Mountain Building at 30°S. Tectonics, 36(11), 2693–2713. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017TC004674

Lossada, A. C., Suriano, J., Giambiagi, L., Fitzgerald, P. G., Hoke, G., Mescua, J., et al. (2020). Cenozoic exhumation history at the core of the Andes at 31.5°S revealed by apatite fission track thermochronology. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 103, 102751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102751

Mackaman‐Lofland, C., Horton, B. K., Fuentes, F., Constenius, K. N., Ketcham, R. A., Capaldi, T. N., et al. (2020). Andean Mountain Building and Foreland Basin Evolution During Thin‐ and Thick‐Skinned Neogene Deformation (32–33°S). Tectonics, 39(3), e2019TC005838. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019TC005838

Mazzitelli, M. A. (2020). Interacción entre procesos tectónicos profundos y superficiales a lo largo de la transecta Cerro Mercedario (32°S), Andes Centrales Sur (PhD Thesis). Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Pérez, D. J. (1995). Estudio geológico del Cordón del Espinacito y regiones adyacentes, provincial de San Juan (PhD Thesis). Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Ramos, V. A., Cegarra, M., & Cristallini, E. (1996). Cenozoic tectonics of the High Andes of west-central Argentina (30–36°S latitude). Tectonophysics, 259(1–3), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(95)00064-X

Reinhard, J., & Ceruti, M. (2010). Inca Rituals and Sacred Mountains: A Study of the World’s Highest Archaeological Sites. Location: The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4m73924p

Ronemus, C.B., Howlett, C.J., DeCelles, P.G., Carrapa, B., George, S.W.M. (2024). The Manantiales basin, Southern Central Andes (~32°S), preserves a record of late Eocene-Miocene episodic growth of an east-vergent orogenic wedge. Tectonics, v. 43, 1-37, doi:10.1029/2023TC008100.

Schobinger, J. (1968). Ruinas incaicas en el Cerro Mercedario, 6770 m: Informe sobre la expedición de Alta Montaña. International Congress of Americanists, XXXVIII, Stuttgart-München, Germany, Verhandlungen, Volume 1:429-434.

Suriano, J., Mardonez, D., Mahoney, J. B., Mescua, J. F., Giambiagi, L. B., Kimbrough, D., & Lossada, A. (2017). Uplift sequence of the Andes at 30°S: Insights from sedimentology and U/Pb dating of synorogenic deposits. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 75, 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2017.01.004

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.