“Brooke received his BSc in Geology from Birkbeck College, University of London in 2015 after collecting rocks and fossils for most of his life. He is currently a PhD student at Hertford College, University of Oxford where he is studying the co-evolution of early eukaryotes and the earth surface environment with Dr’s Nick Tosca, Stuart Robinson and Rosalie Tostevin.”

When someone brings up the topic of geological fieldwork, it conjures images of spectacular far-flung places, remote in time and space. The last thing you would expect is a large shed on a trading estate. Yet this is exactly where I and my colleague, Dr. Rosalie Tostevin, found ourselves in late May 2017. Not the most glamorous of locations perhaps, but this was made up for by the exciting rocks we had come to study. Also, the shed was located just outside Darwin, Northern Territories, Australia, which definitely counts as far-flung.

We stood in a tin-roofed awning, open on three sides to the warm tropical air, it was autumn here and a ‘cool’ 28 degrees celsius. Thankfully we had arrived after the last dregs of the rainy season and been spared the 100% humidity. On either side benches lined with rollers stretched out, one side already covered by trays of rocks another colleague was working on. Still jet-lagged from the 24+ hour trip, it was confusing to see and hear ibis and other tropical birds and reptiles in place of pigeons and seagulls.

A small forklift truck rounded the corner and dropped a pallet of trays in front of us. Steen, one of the Northern Territories Geological Survey (NTGS) staff, hopped out and we began loading the heavy metal trays on the roller table, Rosalie pulling them the full length. Each tray contained ten meters of rock, pulled from the ground hundreds of kilometers away by prospectors drilling for resources. In this case, oil and gas, but everything from iron to gold, diamonds and uranium have been found in this region.

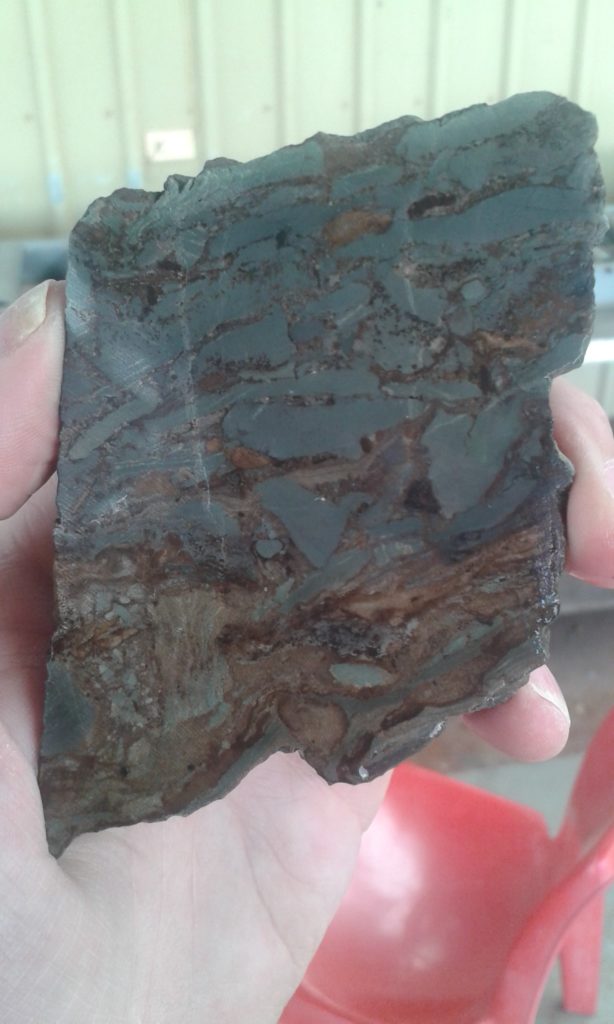

As we popped each lid, some having been sealed for decades, there were gasps and exclamations of surprise. We expected nothing but monotonous black shale, the standard form of hydrocarbon-rich rocks. Black shale was abundant, but so to where sediments in all shades of green, red and purple, swirled with patterns and structures. These structures are the fingerprints of ancient environmental processes, in this case, telling the story of changing sea levels and river courses 1.4 billion years ago.

Above, oxic sediments mixed with fragments of slightly older anoxic sediments, probably deposited by a flood or a storm.

We spent 5 days frantically logging and sampling what amounted to 3.6km of sediment. Imagine walking that distance but having to stop every couple of meters to make detailed notes and collect a sample. It was exhausting, especially in the heat, but also incredible and exciting to be reading the story written in such ancient rocks and translating it to share with others. The story in these particular rocks is of some of the most ancient complex cells and how changing environmental conditions may provide the stimulus for the very first diversification of complex life. An inexorable process that once started, led to all the complex organisms inhabiting Earth today, including ourselves.

It wasn’t all work (even though I do love logging sediments!), we took some time to explore Darwin and have a mini tour of the surrounding area. The beaches are beautiful, though most are haunted by crocodiles, sharks and the fantastically venomous Irukandji jellyfish. We took a trip up the Adelaide River to see some of those crocodiles up close. One-eyed Brutus was the king of that stretch of river, and given his size and ferocity, it was easy to see why.

We are going back to Darwin this coming March, and then on to Canberra. I wonder unexpected rocks and wildlife we will find this time? Being a geologist provides me the luxury of travel that would be otherwise impossible, and this is something I never take for granted.

Above: Sunset over the Timor Sea at Mindle Beach, Darwin. One of the perks of working in the tropics

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.