Lloyd White is a Lecturer in geology at the University of Wollongong. His research focusses on understanding processes that occur during plate collision and plate break-up – primarily using geochronological and structural data to refine computer-based plate reconstructions. While he typically works on land – he reports here from the JOIDES Resolution, one of the International Ocean Discovery Program’s (IODP) ships capable of coring the seafloor in ultra-deep water.

Growing up in southern Sydney meant I spent quite a bit of time by the sea, though never venturing further than just past the breakers, and apart from the odd ferry, I never really spent much time in boats. However, last year I saw a call from the Australian and New Zealand IODP Consortium (ANZIC) seeking participants to join IODP Expedition 369 – titled “Australia Cretaceous Climate and Tectonics” and because of my interest in Gondwana’s break-up, I thought I’d give it a go and apply to join the cruise.

Like all proposals, it took some time to put together, but nowhere near the months I’ve invested (and ultimately wasted) putting numerous fellowship applications together. So, I was really pleased when I received good news from ANZIC – not only did it mean I’d have the opportunity to continue research into the break-up of Australia, Antarctica and India, but that I’d also get the opportunity to work with a bunch of other keen scientists from all parts of the globe, all of whom have totally different backgrounds and research interests.

The aim of Expedition 369 was to obtain a more representative sample suite from high southern latitudes during the Cretaceous to understand more about peak global temperatures, and to better understand the interplay between Gondwana’s break-up and potentially interrelated climate change. It has been an incredibly successful expedition. We managed to collect core from four sites near the Naturaliste Plateau off the SW coast of Australia, as well as one site in the Great Australian Bight. Each site recorded a slightly different aspect of the past, and not only did we recover what we set out to achieve, we also managed to core a near perfect section through the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary – meaning we are one of 18 IODP cruises out of hundreds to do so.

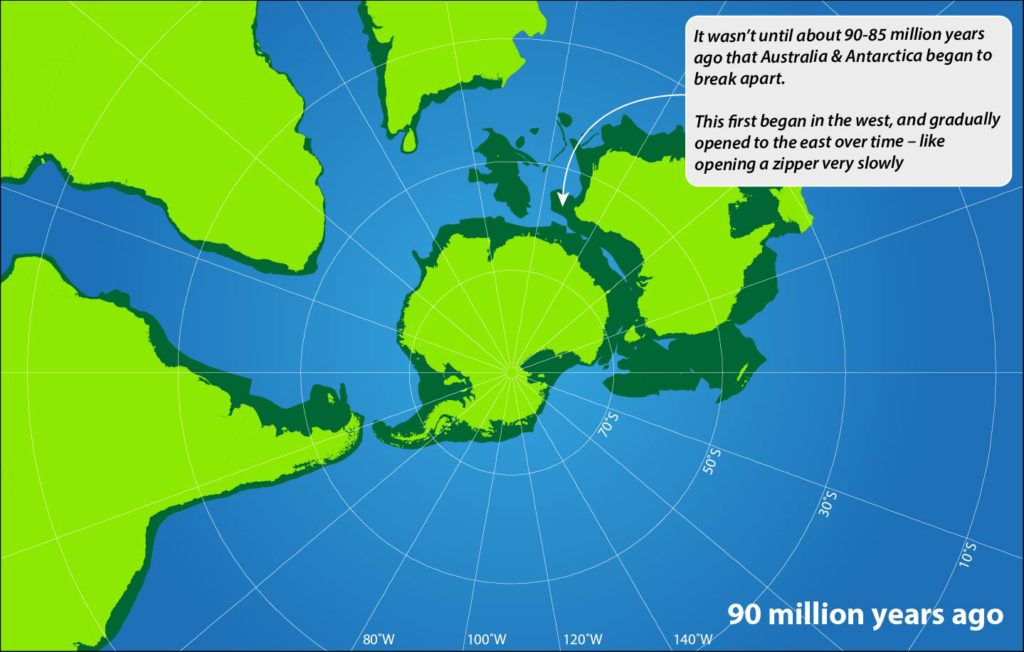

The plate tectonic setting at one of the approximate times of interest for Expedition 369 (Credit: Lloyd White).

My role on the ship has been part of the physical properties and downhole logging teams (i.e., petrophysics). This has involved collecting measurements that are quite different to what I’m used to taking, but it has been a great learning experience. And, while I was initially concerned about getting up to speed with the equipment, we’ve been guided by a fantastic crew of permanent IODP technical staff, who’ve trained us how to operate the equipment and record the information into their computer systems. The lab equipment onboard is actually quite amazing, most of it being custom designed bits of kit that have evolved over time, with a lot of it being semi-automated, meaning there is less chance of introducing human error into the measurements.

Lloyd White shows off some of the samples he’s been working on in the labs on board (Photo credit: Vivien Cumming).

There is an element of repetition in everyday life while we are away. This isn’t just the work schedule (12-hour shifts, 7 days a week for two months…eat, sleep, repeat), but depending on the assigned role can mean the movie Groundhog Day starts to look less like a comedy and more some kind of horror reality show. However, there is also the element of surprise because every core is unique, representing a record of part of the Earth that has not been seen before – and it is this record that all of us onboard work to capture, with half of the material sent to end up in a core library forever, and the other half devoted to detailed paleontological, geochemical and physical tests conducted onboard and later at our labs back home.

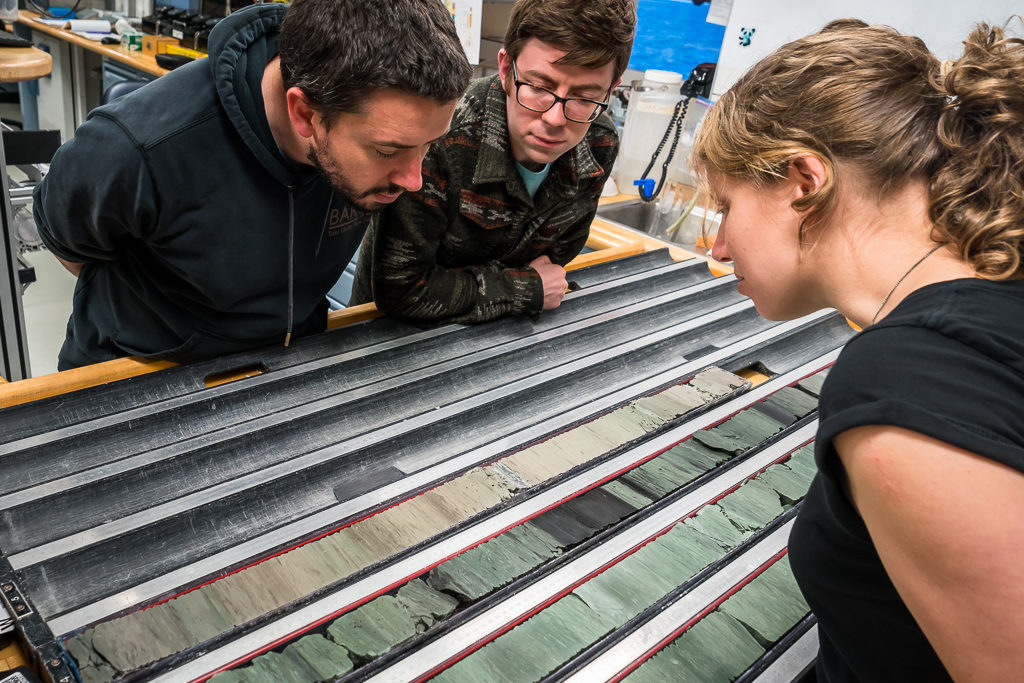

Lloyd examining an oceanic anoxic event at the core table with Carmine Wainman of the University of Adelaide and Sietske Batenburg of the University of Oxford (Photo credit: Vivien Cumming).

While everyone on the ship has some interest in a particular aspect of the cruise, we also understand that there is also a responsibility to ensure that the data is there for another scientist who may in the future want to test some hypothesis that has not yet been conceived. It has also meant that we’ve been able to generate a broad suite of real-world datasets that can in future be incorporated into undergraduate teaching.

Being part of a large scientific team with various overlapping specialties and interests is perhaps why IODP and its predecessors have been so successful. I just hope that the respective Governments involved with funding this program continue to support this international, interdisciplinary research.

I guess it’s not quite the same as working on the International Space Station – but for most of us geoscientists who tend to focus our sights down at the Earth, rather than looking upwards to the stars, collecting hundreds of meters to kilometers of core from great depths (up to ~4 km in our case) is quite amazing. This is particularly the case if we accept that we still have a lot to learn about the evolution of our planet and when most of it is covered by ocean, and we need the ability to sample not just the top of the seafloor, but also what lies beneath.

Vivien Cumming is an Earth scientist turned photographer and writer who documents geological expeditions for the media and helps scientists tell the stories of their research. For more information please visit her website (viviencumming.com) or follow her on twitter and instagram @drvivcumming

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.