Erin Martin is a PhD student studying at Curtin University in Perth with Professor Bill Collins and Professor Zheng-Xiang Li. Her work employs zircon geochronology and Lu-Hf isotope geochemistry to evaluate plate tectonic processes and paleogeography of the Neoproterozoic, with a focus on the orogens of Argentina and southern Brazil. Read more about her work here.

The Sierras Pampeans are a series of north-south trending mountain belts in central Argentina that formed around 500 million years ago. It’s thought that these mountains formed by subduction of oceanic crust beneath continental crust, the same way the Andes are forming now. However, the Sierras Pampeans formed part of the supercontinent Gondwana when the continental blocks that make up South America had collided for the first time.

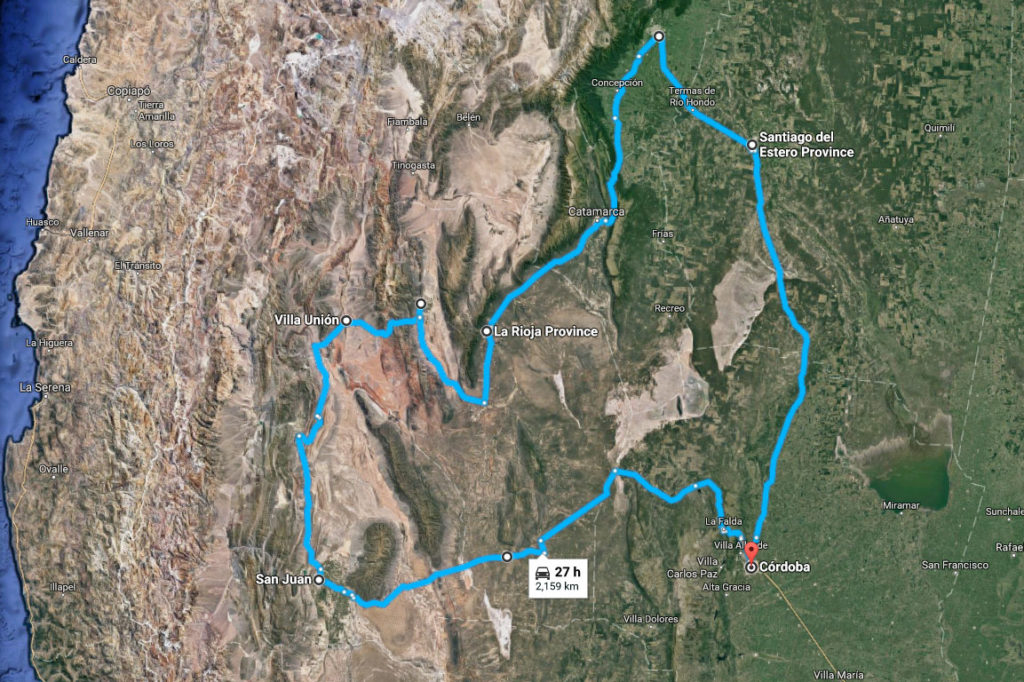

In 2016, my PhD supervisor Bill and I travelled to Argentina for ten days to study and sample the Sierras Pampeanas. The aim of the work was to better understand the plate tectonic processes leading to their formation. Our journey took us over 2000 km on a loop from Cordoba in central Argentina, west as far as the San Juan Province and the billion-year-old terranes of the Argentine Precordillera. Along the way, we met me the locals, broke the clutch in our 4×4, and enjoyed the famed Argentine asado and Malbec.

Completing fieldwork in a foreign country is an incredible opportunity, experiencing different cultures and landscapes really are wonderful but it’s not without its difficulties. For us, a pair of non-Spanish speaking Aussies, the first hurdle was finding a sledge hammer, which proved especially difficult when the first one we purchased snapped a handle on the first rock it hit! So after visiting countless ferreterías (hardware stores) asking for a martillo grande (big hammer), we were eventually on our way, heading north from Cordoba.

The landscape in this region of central Argentina is stunning. The valleys are dominated by farmland, from Gauchos mustering cattle, to olive groves and vineyards, to smouldering sugar cane plantations. As we drove along the valleys, the steep mountain ranges crept out of the smoky haze into view. The easternmost ranges are heavily vegetated, covered in this forests of gum trees, which made us feel right at home. On our first few days in the east, the rocks were, as Bill put it, fubar’d (see Saving Private Ryan). What were once sedimentary rocks, deposited beneath the around 600 million years ago, were now a folded, sheared, melted mess intruded with a variety of granites, dykes and veins. What was left of the sedimentary rocks was complexly folded and foliated rock that had been metamorphosed (amphibolite facies), and composed of quartz, garnets, biotite and sillimanite. This easternmost region of the Sierras Pampeanas is littered with 530-500 million-year-old granites. The deformation and metamorphism and granites are all linked to the initiation of subduction and the Pampean Orogen, an ancient Andean-type mountain chain.

After journeying north for a couple of days, we began to drive west. With every range we crossed, the climate became dryer, and the plants changed from trees to briar, to cactus. The rocks seemed to change over a similar gradient. We reach La Rioja for an overnight after a few days in the high-grade stuff. Eager to get on the road the next morning, we were disappointed to find that the clutch our Ford Ranger was no longer with us. The rest day allowed us the opportunity to explore the town a little, finding a restaurant with delicious asado – juicy Argentine beef cooked over an open flame. Paired with a bottle of local Malbec, it certainly made the delay enjoyable. So after a forced rest day to collect our thoughts, consult our notes and have our vehicle repaired, we once again hit the road.

Heading west, the sediments had become less deformed grading into lower amphibolite schists. As we left La Rioja, the 600 million-year-old sedimentary rocks were behind us and we had reached the Ordovician (~480-470 million year old) granites of the Famatinian Orogen. The Famatinian granites outcrop intermittently between brilliant red successions of Permian age strata. As my PhD is focused on 1000-500 million-year-old tectonics, we made the trek from La Rioja to Chilecito in a day via RN 40. This road was spectacular and warranted numerous photo stops.

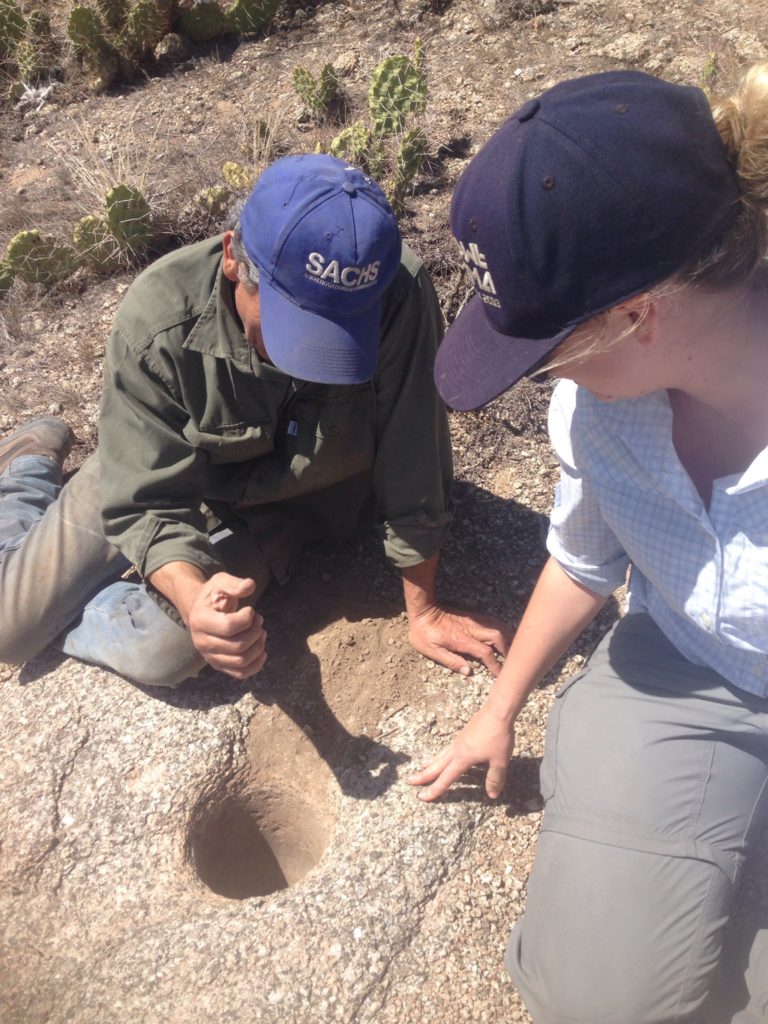

A Chilecito local showing me where the Incan’s used the granite to grind maize hundreds of years ago

The RN 40 cut through the Famatinian rocks to the billion-year-old rocks of the Maz Terrane. This far west in Argentina, the elevation was starting to increase, and we were well and truly within the rain shadow desert of the Andes. The ancient Maz Terrane and the associated Mesoproterozoic blocks that lie to the north and south of it smashed into the paleo-coastline of South America during the Famatinian Orogen. These blocks are especially interesting as they are made up of rocks with properties very similar to rocks of the same age from the southeastern USA. Some researchers suggest that the Maz Terrane and it’s Mesoproterozoic buddies broke away from the USA coast and drifted across a wide ocean before colliding with South America. Others are convinced their source is a lot closer to their current home. We sampled sedimentary and metamorphic rocks and granites that intruded fold hinges of the deformed rocks to evaluate how the Maz Terrane evolved thought time and space and how it links to the other rocks of the Sierras Pampeanas.

Further south, just east of the beautiful city of San Juan, we visited the Pie de Paulo, another Mesoproterozoic terrane. In this region, the older metasediments lie beneath limestones and marbles that were deposited on a Cambrian (540-490 million-year-old) carbonate platform.

I was lucky enough to call Argentina my office for ten days and it was only just enough time to scratch the surface of this incredible place. Now, my work continues back at my real office in Perth as I analyse the samples we collected and discover the story of the formation of the Sierras Pampeanas.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.