Sandie Will is the Manager of the Geohydrologic Data Section within the Data Collection Bureau at Southwest Florida Water Management District. She has been a hydrogeologist for almost 20 years and is licensed by the State of Florida. She received her Bachelor of Science degree from the University of South Florida and Master of Science degree from the University of Florida with a specialization in Water Resources Planning and Management. She also runs the “A Day in the GeoLife” series and other blogs on her Rock-Head Sciences website and writes fiction novels including her soon-to-be-released, The Caging at Deadwater Manor.

Every year, fieldwork becomes a thing of the distant past for me. I have a passion for being in management and helping staff meet their career aspirations, but it doesn’t provide the day-to-day fieldwork opportunities. So, to fill this void, I spend many of my vacations (such as my last one, looking for things to do in Omaha) at localities prime for geologic exploration, and my unsuspecting family members are usually dragged along with me. Such was the case last summer while I attended a family reunion in Indiana. This time my victims were my sister-in-law, Marianne — who, as luck would have it, turned out to be a geology prodigy; and my husband who now has a good story to tell, but will probably never let me on a plane with him again.

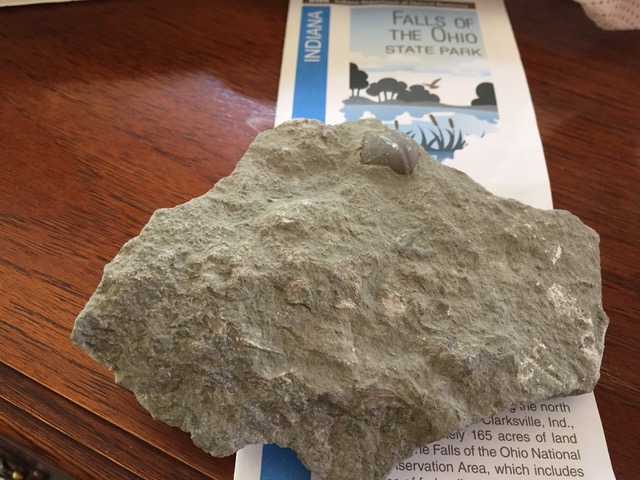

The Falls of the Ohio State Park is located in Clarksville, along the southern border of Indiana near Louisville, Kentucky. The geologic interest of this park lies in the massive 390 million-year-old Devonian fossil beds that were exposed from the damming of the river. During the Devonian Period, a continental sea existed in this area which was inhabited by various marine life including trilobites, brachiopods, corals, sponges, echinoderms, crinoids, blastoids, fish and bryozoans, the skeletal remains of which were preserved in the limestone. Visitors can stop by an Interpretive Center to learn about the history and then can walk on the fossil beds. For more information see their website at Falls of the Ohio State Park. For more in depth stratigraphy and fossil in formation, see Silurian and Devonian Geology and Paleontology at the Falls of the Ohio, Kentucky/Indiana (there are some informative fossil plates at the end of the paper).

I had visited this park long ago and before I knew much about geology. So, my thought was to join in the family reunion festivities and then steal away for a few hours to study this paleontological gem closer. Time was running out, but a few hours before I had to board the plane, Marianne kindly offered to take me to the park. Little did she know the depths of my geologic geekiness until we came upon two piles of rocks and fossils at The Falls.

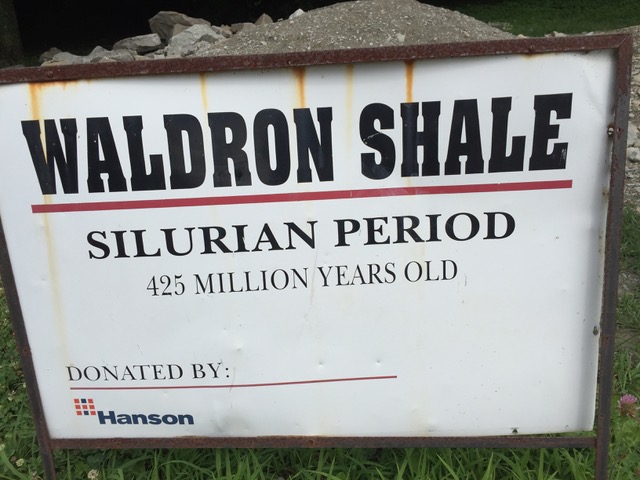

I had read that the park allows fossil hunting from designated piles at the back of the Interpretive Center, but I had no idea that one pile would be Devonian age and the other would be Silurian, dating back 425 million years old (I believe these might have been brought in from a local quarry). At first glance, I was a bit disappointed with the selection, but as I continued, I collected more and more fossils, pyrite and purple fluorite in outright jubilation. Of course, during all this time, I was “educating” Marianne on the “fortune” we’d been bestowed and that the only fossil missing was brachiopods. In all of my travels through the years, I had never been able to find even one. She asked me to describe it, and as we ventured forward, she showed me a fossil she found. I continued with my own search and half-heartedly glanced at her hand. Surely, there was no way she could find a brachiopod.

Not only did Marianne find one, she found numerous. She was easily plucking them from the pile, leaving me with my mouth agape. I think I even leapt. She was then dubbed the brachiopod queen, and we carried our loot over to the car before going to see the fossil beds.

Behind the Interpretive Center, there’s an observation deck to view all of the sprawling fossil beds exposed in areas where the water level is low. Beyond them, is the long dam, and even further is the city line of Louisville and an old railway bridge.

I walked down the Jeffersonville Limestone along the riverbank to the fossil beds with relative ease, and just as all of the park information promised, abundant fossils were at my feet – everywhere. Most of the time when I’ve studied geologic rock formations, I’ve examined a road cut or the typical vertical layer cake. This phenomenal site allowed me to see the marine life during the Devonian horizontally as I walked along the ancient sea floor. Numerous visitors walk on these fossil beds every year, and I’m sure they have no idea of the astounding significance of this site.

I left the park feeling very satisfied that day, not to mention proud of my sister-in-law. However, I did learn another interesting fact about these fossils. I’m not sure why, but they set off explosive alarms while going through airport security. Unfortunately, my husband had them in his backpack, leading to an embarrassing full-body search. Serious faces came in droves to test the “explosive” fossils and question us. And just as I was about to step in to tell them to arrest me and not my husband, they gently placed the fossils back in the bag and sent us on our way – only pausing to tell me how cool it was that I was a geologist and asking me questions to gain more knowledge on the park and fossils.

All for the love of geology…

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.