Sheree is a PhD candidate at The University of Adelaide researching the plate tectonics of supercontinent Gondwana in Madagascar and India. You can stay up to date with her research here and follow her on twitter @geoSheree.

Understanding how the Earth’s plate tectonics have evolved and changed over time has always fascinated me. When I was looking around for potential PhD projects, I knew I wanted to do research in plate tectonics that existed hundreds of millions of years ago, and I wanted to travel somewhere exciting. After travelling to some incredible places within Australia during my undergraduate and honours at Monash University in Melbourne, and as a geologist for Geoscience Australia, I knew it was time to venture abroad. Professor Alan Collins and his research team at The University of Adelaide was the logical choice.

Our research group works on the tectonic evolution of past supercontinents such as Gondwana, in places as varied as Ethiopia, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Zambia, Madagascar and India. The bulk of my PhD work is looking at Madagascar – a region which occupied a key position in the centre of the supercontinent Gondwana when it was being formed. An opportunity also came up to do field work in India, which until recently (geologically speaking), was connected to Madagascar.

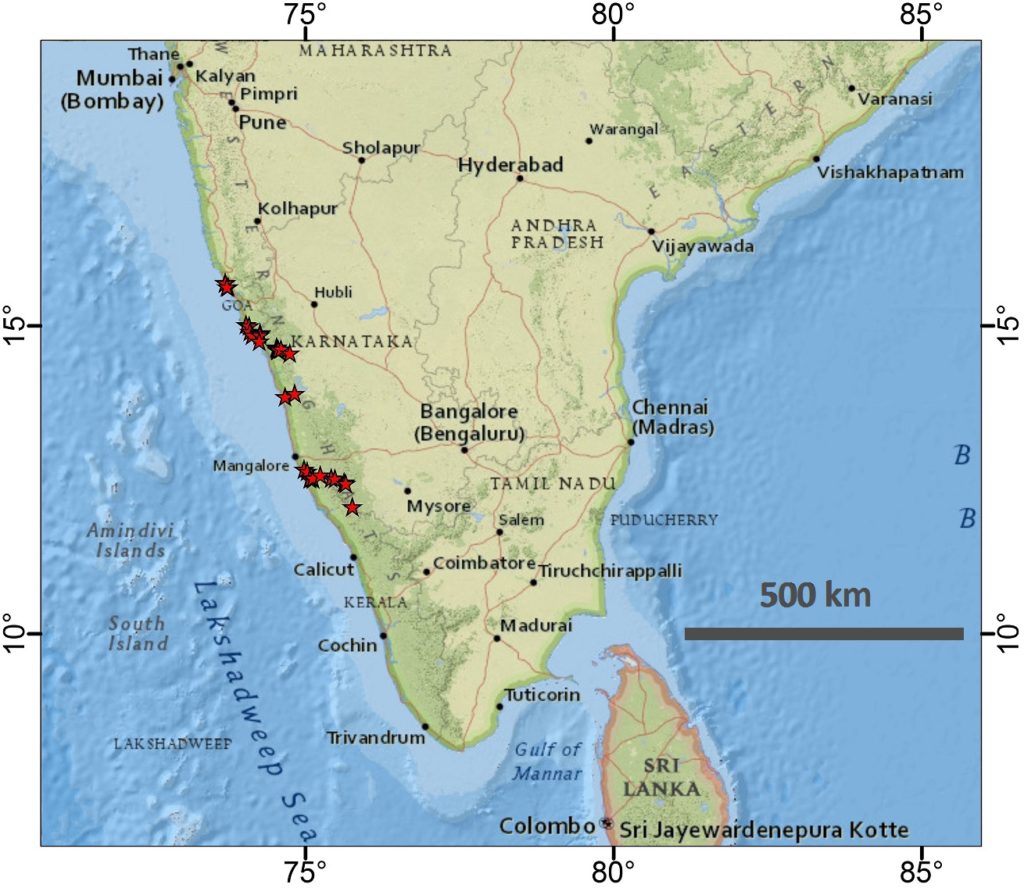

In January 2015, only a couple months into my PhD, we set off for Goa in west peninsular India. Goa is a relatively touristy area and because we had a few days before meeting up with our Indian colleagues, it was the perfect spot to settle in. At this stage, our field team consisted of my PhD supervisor Alan Collins and an honours student from the University of Adelaide, Bill Mansfield.

Some of the best rock outcrops in Goa are near the beach which is conveniently where most of the bars and restaurants are too. Alan has a knack for choosing great field locations.

Sandstone outcropping at the beach in Goa. We accidentally stumbled upon several nudist sun-bathers while trying to find good outcrop along the beaches.

We hired motorised scooters to visit a few outcrops as this was the best way to get around the chaotic streets and roads of Goa. Alan and Bill looked right at home on their scooters while I nervously tried not to crash. I think the locals must have detected my apprehension as they always managed to zip past me or let me go in front just in time for me to keep up with the others. We rode through some beautiful countryside too which was far more relaxing, and we took ferries across some of the rivers.

Bill and I on one of the many ferry crossings. We never got charged for the ferries which seemed really strange to us. Photo: Alan Collins

A lot of the rocks along the beaches were sandstones which are good rocks to find zircons. Zircons are tiny grains inside rocks that we can extract and then zap with a laser to work out how old they are. Our aim was to collect a bunch of these rocks to work out their ages and where the material might have been transported from. There are conflicting ideas about these rocks, with some researchers suggesting they are more similar to rocks in Madagascar and others suggesting they are more closely related to rocks further to the east in India. In resolving this issue we hope to better understand how and when Madagascar and India joined up hundreds of millions of years ago.

After a couple days in Goa, our Indian colleagues including Professor Shaji and four of his students from the University of Kerala, met up with us where we would then set off further to the south. From here most of the outcrops were found in creek beds, quarries or road cuttings.

Road work sites were great places to get freshly exposed rocks and to see great sunsets. Photo: Alan Collins

Once we left Goa there were hardly any tourists which meant we often attracted stares from interested locals. There were several instances where we would be having lunch or visiting a local attraction and some locals would want their photo taken with us.

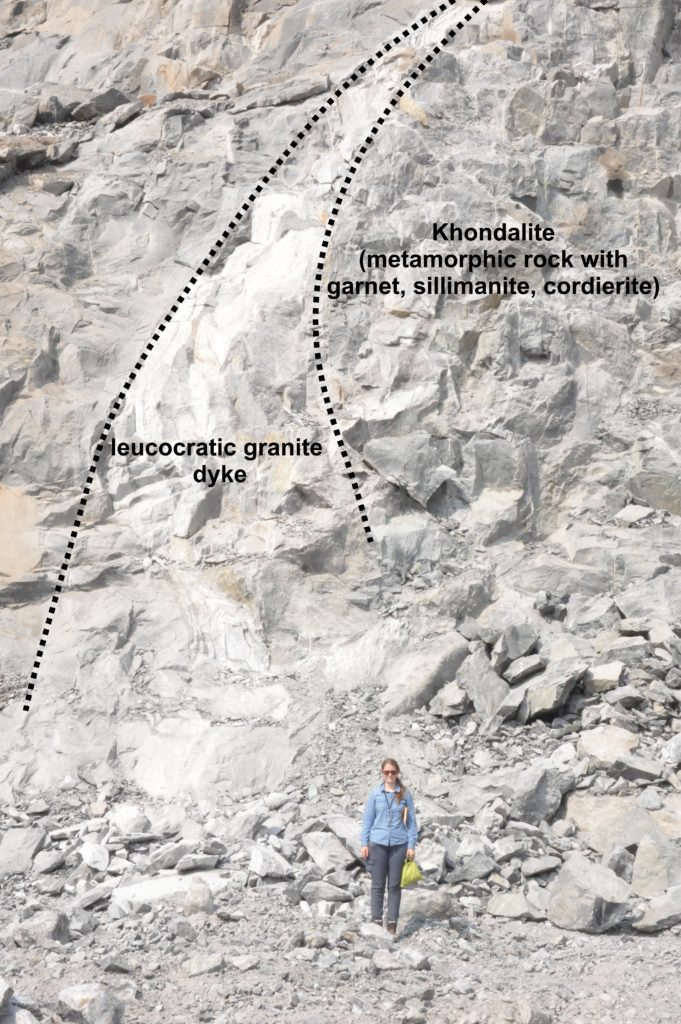

Quarries are great for getting a sense of larger scale variations in rock types or structural trends. In this quarry we could see an intrusive dyke into the Khondalite country rock. Photo: Alan Collins

Some young girls wanted their photo taken with me when we visited a Hindu temple, I’m still unsure if I felt more like a celebrity or a circus attraction. Photo: Alan Collins

We were working in a creek bed just off a road when the local school had finished for the day. Our Indian colleagues told them we were filming a movie and that we were really famous actors from overseas. Suffice to say they were super excited when I asked if I could take this picture.

One of the best things about travelling as a geologist rather than as a tourist is that you’re often accompanied by colleagues who live in the area. This meant we got a better understanding of the Indian culture and their customs. We got to try some really great Indian food – most of the time I had no idea what we were ordering so it was great to have them show us all how it’s done, including learning how to eat with our hand!

A typical serving of Indian food consisting of several curries, a tonne of rice, naan and fish – all served on a banana leaf.

Since this field trip we have processed and analysed zircons from these rocks which tell us that they have similar ages to rocks found along eastern Madagascar and to other rocks in south-central India. Some of this work will be presented at the upcoming International Geological Congress in Cape Town. This is only a small piece of the puzzle and with field work planned in Madagascar for September 2016, I hope to better understand how the plate tectonics of these regions have evolved over time.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.