There are many ‘TravelingGeologists’ from history that have left an indelible mark on our understanding of earth sciences as well as on society. You can read more about the seminal geologists of the past here. This post comes from Kellen Gunderson. Kellen received his PhD from Lehigh University and now works for a large energy company in Houston, Texas. You can read more from Kellen here.

For those that love both geology and adventure stories, you can’t do much better than stories about the “old school” field geologists in the past. Many of these early geologists ventured into places that were truly unknown and they had to piece together the geology of region where no one had gone before- where no maps existed, no regional stratigraphy was there for context, and (as was often the case) no civilization was in sight. The romanticism of these stories is enhanced by the fact that they occurred sometime back when the world was captured in black and white (or sometimes on canvas, if you go back really far) so tales of early geologists blend hazily with those of explorers like Shackleton or Mallory.

One of my favorite of these stories is of the petroleum geologists working for Standard Oil of California (SoCal) that explored the Arabian Peninsula in the 1930’s. When they arrived in Saudi Arabia, these geologists came to a country that almost no westerner had seen, a country with no modern infrastructure, and within a few years deciphered the geology and made the largest discoveries of oil in the world. Needless to say, there were numerous geologists and engineers that contributed to this massive undertaking, but the most famous of them all and the most influential in the history of Arab oil exploration was a man named Max Steineke.

SoCal negotiated a concession with the Saudi Government to explore for oil in the summer of 1933 and by that fall the first geologic field expedition arrived. Max Steineke arrived in Saudi Arabia in 1934, in time for the second of the SoCal exploration field seasons. He immediately made a big impact. As Wallace Stegner said in his history of the Saudi oil exploration and discoveries,

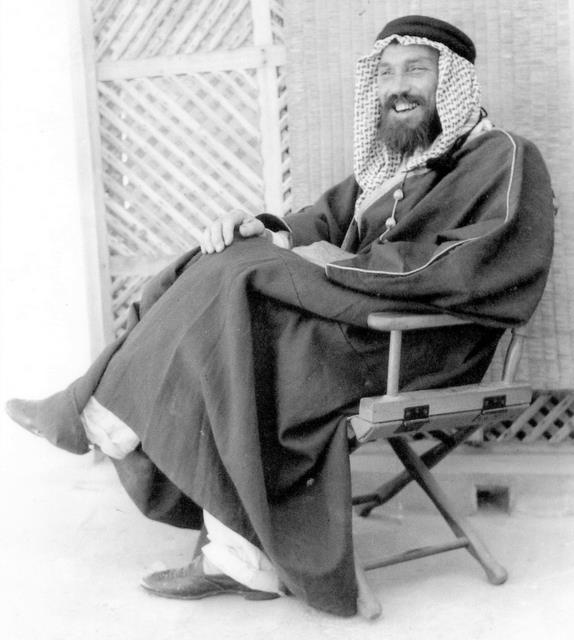

Max Steineke in Saudi Arabia. Steineke and the other geologists adopted the dress and look of the local Bedouins with whom they worked. Image from Wikipedia.

“Steineke was ‘no son of a bitch for civilization’…It is conceded by those who worked with him that Steineke was the man who first came to understand the stratigraphy and the structure underlying eastern Arabia’s nearly featureless surface. As a field geologist he rated with the best anywhere, and as a man, a companion, a colleague, he could not have been more adapted to the pioneering conditions he now encountered. Burly, big jawed, hearty, enthusiastic, profane, indefatigable, careless of irrelevant details and implacable in tracking down a line of scientific inquiry, he made men like him, and won their confidence.” (1)

Steineke had graduated from Stanford University in 1921 and had previously completed work for SoCal in New Zealand, Colombia, and Alaska. When he heard about the Arabian venture he begged the company managers to send him to the Arabian Peninsula.

Max Steinke doing field work in Alaska. Wallace Stegner said, “he was no son of a bitch for civilization.” He loved the outdoors and the spirit of adventure that went with being a petroleum geologist of that era. (photo source).

When Steineke arrived in 1934, conditions in at the camp where the SoCal personnel lived were still very primitive. The geologists originally lived in tents in their camp near the Arabian Gulf on the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia. Eventually they upgraded to mud huts and, after a few years, the comforts of western life began to creep into the camp. Eventually, even air conditioning units were imported. But in those early days, the field expeditions lived rough. Many of the geologists, Steineke included, grew long beards and dressed in the garb of the native Bedouins. They had many of the local Saudis working for them and the SoCal personnel took a keen interest in learning and emulating the local culture and customs.

The geologists conducted regional reconnaissance via an imported aircraft. One or more of them would fly patterns over the desert looking for interesting structural or stratigraphic features in the barren land. Steineke and the others were searching for the surface expressions of anticlines that would serve as traps for hydrocarbons deep in the subsurface. This was done by either by locating a domal uplift on the surface or inferring the presence of anticlines in the subsurface by mapping surface bedrock patterns. When the airplane spotter located a feature that seemed promising they would gather up a land crew that would travel to the location by camel or via specially modified trucks that had been constructed to travel across a desert landscape and start mapping the geology.

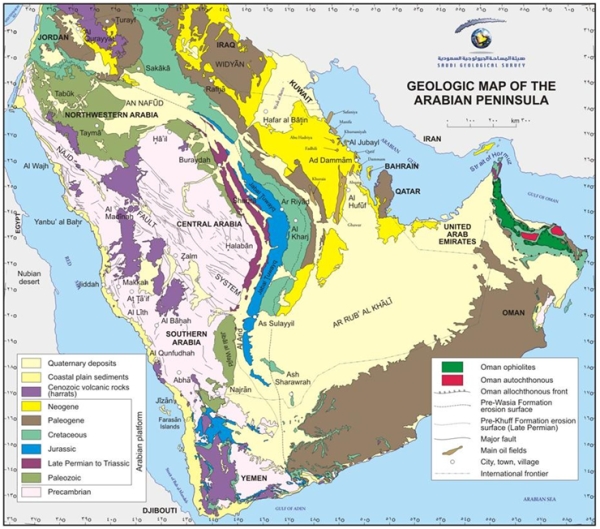

Geologic map of the Arabian Peninsula. The generalized geology of Saudi Arabia consists of mostly Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks that are gently and monoclinally dipping east toward the Arabian Gulf. These rocks lie on top of Precambian basement that is exposed in the west. Steineke’s 1937 traverse across the peninsula exposed him to the whole geologic succession of Arabia and was instrumental in his unraveling the geologic history of the area.

By 1935 Max Steineke and the other SoCal geologists located several promising locations for drilling wells along the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia. The first wells were drilled in 1935 and 1936. Although the wells were promising and had small shows of hydrocarbons, none of them indicated a large economic accumulation of oil. By 1937, the SoCal management back in California was beginning to become restless. The Arabian venture was costing a lot of money, but so far there was very little to show for it. In the spring of 1937, Max Steineke undertook an important field expedition that proved to be critical to the understanding of the regional geology. Steineke, accompanied by a colleague named Floyd Meeker, crossed the Arabian Peninsula from the eastern gulf coast to Jiddah on the Red Sea. This traverse exposed Steineke to the whole stratigraphic succession of Arabia and allowed him to view the contact between the basement rocks and the sedimentary cover rocks. This trip, punctuated by several adventures, was like a revelation. The geology of the Arabian Peninsula began to crystallize clearly in Steineke’s mind.

The Damman #7 well discovered oil in Saudi Arabia in March 1938. This well was the first to make a significant discovery that proved the potential of the Arabian oil province. It came just in time, after a series of failures, SoCal management was ready to pull the plug on the whole Arabian exploration venture when #7 came in big.

Later in 1937 SoCal began drilling a well called Damman #7. Steineke, now the chief geologist of the venture, and the others decided that it would be a deep test well. They would go deeper than the other wells and test the “Arab Zone” formation. Drilling was slow and expensive and executives in California were impatient. In November, 1937 while drilling Damman #7, SoCal decided to pull the plug on the whole venture. They sent a message to Steineke telling him to report back to San Francisco. Steineke went back to California and argued with management, what he had seen on his trip across the Arabian Peninsula convinced him there was oil to be found there. He convinced management to at least wait for the results from Damman #7, which was still drilling at a slow pace.

Steineke’s persistence paid off. In March 1938, the Damman #7 well penetrated the Arab Zone and discovered oil. The well was soon producing 3,800 barrels a day. The SoCal geologists could now convince their managers that there was oil in Arabia and the Saudi oil industry was born. Over the next decade, Steineke’s insights regarding Arabian geology led to the discovery of the giant oil field of Saudi Arabia: Abu Hadriyah, Abqaiq, and Ghawar. In addition to the oil discoveries he made, Steineke’s contributions to our geologic understanding of Saudi Arabia endure. His papers on the stratigraphy of Saudi Arabia, emanating from his 1930’s field seasons, remain as the foundational work of Saudi geology.

References:

(1) Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil, by Wallace Stegner, 1971

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.