Graham is a petroleum geologist working for a small oil & gas company based in London, UK. Having completed a BSc in Geology at Exeter University in 1985, Graham has spent much of the last 30 years working on the prospectivity of many areas, including the UK & Ireland, North Sea, much of mainland and offshore Europe, Africa, and beyond. As part of his work, Graham is occasionally called upon to undertake field trips to study rocks that might be geologically analogous to the oil and gas reservoirs he is working on. Graham’s current geological interests include turbidite and carbonate rocks and the rifted basins that they were deposited in, as well as a particular fondness for the geology of Namibia.

Probably the best field trip* in the world ever!

(*and it wasn’t even a field trip)

Part 1 of 3: Las Vegas to Los Angeles

It was two years ago that we agreed, to celebrate my son’s completion of his GCSEs, that we should have an extra-special family summer holiday. My son decided that he wanted us to do an American road trip, and between him and his mother, they came up with a list of places to visit. Las Vegas, Palm Springs, Los Angeles, San Francisco… All I had to do was come up with an itinerary… I must admit that the thought of Las Vegas appalled me. I had a lack of enthusiasm for yet another journey to the USA (perhaps my enthusiasm was dimmed by too many trips to Houston!), coupled with an almost complete lack of geographical knowledge of the south-western USA. However, a quick dip into Google Earth suggested that it would be possible to link the above cities with some very interesting geological localities indeed, and my mood suddenly swung the other way! Traversing parts of the relatively stable Colorado Plateau, the more heavily-deformed “Basin and Range” Province, as well as the tectonic crush zone that is the Californian Pacific Coast, this had the makings of a trip of a lifetime!

And so it came to be that in August 2014 we flew into Las Vegas. My geological appetite had already been piqued during the flight over, with almost cloudless skies giving spectacular views of the Greenland fjords and icecap, the vast tundra wastelands of Canada, the frac-pad speckled landscape of mid-western USA, finally giving way to the more crumpled and incised terrain of Utah and Nevada and a tantalizing distant glimpse of the Grand Canyon.

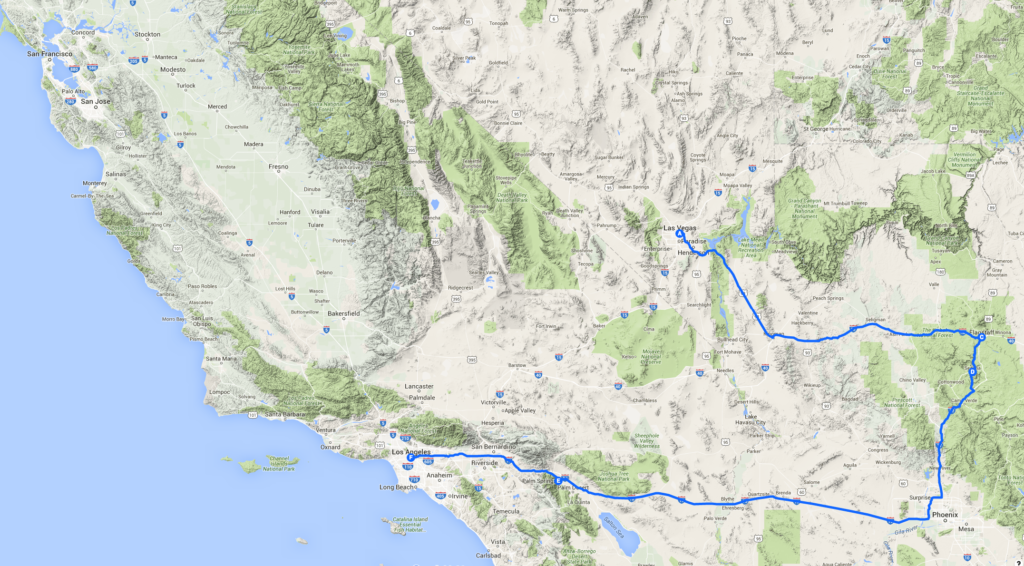

Vegas isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, especially in high summer with temperatures topping 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The oil and gas exploration geologists amongst us, well aware of risk vs. reward scenarios, will want to escape the gaudy bling of the casinos and shopping malls as soon as possible. But Vegas is inexpensive to fly to and (on account of subsidy by the gambling industry) is a remarkably cheap place to stay. It is also ideally located for a road trip taking in large chunks of Nevada, Arizona and California. I’ve written this piece about the first leg of the road trip, from Las Vegas to Los Angeles – see the map below.

And so we set off the following day from Las Vegas, heading for the southern rim of the Grand Canyon. Just outside Vegas we took a short detour to marvel at the geotechnical engineering of the Hoover Dam. Here I started to get mild pangs of anxiety trying to take in all the rocky outcrops, most of which were confusingly unfamiliar. As a geologist, I always hate it when I cannot instantly interpret an outcrop, and this stop was he first of many outcrop geology overloads.

A word of caution – although distances on the map look deceptively short, the Grand Canyon southern rim is a good 200 miles distant from Vegas. The Grand Canyon itself is a staggering 277 miles in length, something I never appreciated before this visit. With a relatively leisurely drive taking in parts of the old Route 66, we didn’t actually get to the southern rim until late afternoon. Approaching from the south across a deceptively flat featureless landscape, nothing really prepares you for the gaping chasm of stratigraphy that is the Grand Canyon itself. Unfortunately, nothing really prepares you for the traffic jams and the masses of gawping tourists either. Recommendation – if you haven’t got time to take several days hiking down to the bottom and up again, bypass the visitor centre and continue driving eastwards along the southern rim road. It winds along for a good 25 miles atop the edge of the canyon, and there are countless car-parking places, most of which are near-empty, each affording spectacular and varied views.

Given the extraordinary length of the canyon, you’re unlikely to see more than a tiny bit of it, even if you stay for days. From a number of vantage points, I was able to take in some of the larger features and formations, with the help of interpretation boards and leaflets. Binoculars would have helped! The stratigraphy here consists of thick, almost horizontal layers of Palaeozoic sediments – sandstones and limestones – unconformably overlying basement metamorphic rocks of Pre-Cambrian age. The unconformity can be clearly seen in the bottom of the canyon. The sandstones at the top of the canyon comprise distinctive paler yellow continental fluvial and aeolian sands extending up into the Permian (more of these later). The whole sequence, barring the odd fault, seemed from our vantage point to be almost completely undeformed – it is part of a giant stable block (the Colorado Plateau), wedged like a table between the Rocky Mountain orogenic belts to the north-east, and the younger, crumpled “basin and range” terrain to the south-west.

Musing on the origins of the Grand Canyon, it seemed to me (after just an hour or so’s geological interpretation!) to be very young feature, geologically-speaking. A series of prominent back-stepping terraces and “canyons within canyons” suggested to me several rapid pulses of uplift, rather than steady uplift and erosion coupled with simple variations in lithology. Several other observations during this trip led me to a similar conclusion, but I am sure much academic work on this has been published down the years and that there are many other more plausible and carefully thought through interpretations!

Continuing eastwards, and thence south to Flagstaff, the road passes some wonderful lesser gorges and slot canyons, before skirting the edge of the Painted Desert, so called because of the varicoloured iron-stained strata, this time of Triassic age. The route then heads into a landscape increasingly dominated by volcanic cones, lava flows, and the brooding volcanic massif of Humphrey’s Peak, at over 12,000 feet, the highest point in Arizona.

Flagstaff, which is located on the flanks of Humphrey’s Peak, is at a deceptively high altitude, with a pine-forested, almost alpine backdrop. Unfortunately, by the time we arrived, the clouds were down, the rain was pouring and the place had all the atmosphere of Aviemore, Scotland, on an averagely dreary wet day.

The following day we drove through rain-drenched pine forests, before the road dropped precipitously into the Oak Creek Canyon and the little town of Sedona. Apparently Sedona was the inspiration for the town of “Radiator Springs” in the move “Cars”, and is famous for its backdrop of ochre-red sandstone cliffs, which have become eroded into a fantastic series of rock turrets, spires and arches. Located on a fault line defining the junction between the flat-lying strata on the stable Colorado Plateau to the north-east, and the tectonically-crumpled “basin and range” terrain to the south-west, the sandstones here are Permian-aged fluvial and aeolian deposits that are remarkably analogous to our own Permian Leman sandstone reservoirs in the Southern North Sea. Unfortunately, it was still raining heavily, the clouds were down, and we saw almost none of this, the disappointment being compounded by the numerous “high risk of forest fire” signs dotted along the roadside.

From Sedona, a spectacularly winding road took us westwards through more pine-clad mountains and the bizarre copper-mining town of Jerome (old timber buildings perched precipitously on stilts on a hillside) and then into the Mohave Desert. A landscape now dominated by rugged treeless mountain ranges, fringed by huge alluvial fans, and dotted by tree-sized cacti.

By now the sun was shining, as might be expected in what is allegedly one of the driest areas on the planet. However, as we drove on and on, westwards towards California, the clouds began to build again and dust devils were being whipped up by the wind. The geology too was becoming more chaotically-contorted, fractured and folded, signifying a tectonic front coincident with the approaching storm front. On the interstate motorway just across the border, the traffic came to a standstill as flash floods swept across the carriageway. My son and wife were by now outraged at this dreadful holiday weather, but for me, it was a spectacular and mesmerising geological experience, and gave an insight into the formation of all those alluvial fans. Not only were the gullies awash with boulder-choked torrents, but the intervening flat areas were covered in vast expanses of rapidly-moving water. Now I have worked the Triassic oil and gas reservoirs of the UK Southern and Central North Sea for many years now, and am quite familiar with the concept of a “sheet-flood” sandstone, but I had never, ever expected to see a live one! By the time we crossed the San Andreas Fault, and arrived in the desert resort of Palm Springs, the storm had subsided, but the roads were flooded in places with up to a foot of water.

Despite its desert location, Palm Springs isn’t in itself a particularly geologically interesting place, although the springs themselves reputedly arise via fault-related fracture systems. The interest lies in the staggering variety of landscapes and geological features associated with the San Andreas Fault which bisects a pull-apart basin from northwest to southeast through the Coachella Valley just outside the town. Immediately to the south, a trip up into the San Jacinto Mountains via cable car took us from the desert to cool sub-alpine conditions within minutes. The precipitous northern edge of San Jacinto Mountain over-looking Palm Springs, at around 10,000 feet elevation, is the highest escarpment in the entire USA. The rocks are granites of Cretaceous age, but the uplift was astonishingly accommodated within the last 5 million years alone as a result of localised compressive “pop-up” along the San Andreas Fault.

Later that day we drove into the nearby Joshua Tree National park, ostensibly to pay homage to the U2 album which shares its name. Aside from thousands of ubiquitous joshua trees, the area is underpinned by more Cretaceous granites, which have eroded into a wonderful landscape of rounded boulders, slabs and inselbergs. In some places the undulating contact between the granite and the country rocks is clearly visible in the mountainsides. As an added bonus, Keys View provides a panoramic viewpoint in which the Pacific and Northern American tectonic plates can be seen in juxtaposition across the San Andreas Fault, which cuts like a knife through the Coachella Valley. There are not many places in the world where you can get a view like that. Simply stunning.

From here we headed to Los Angeles and beyond – which I’ll write about in the next instalment!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.