Jess Kapp is a senior lecturer and the associate department head in the department of geosciences at the University of Arizona. In addition to teaching geology, she writes fiction and non fiction, and is currently finishing a memoir about her high altitude field adventures in Tibet. You can find her at http://jesskapp.com, on Twitter @jess_kapp, on the Huffington Post education blog, and on Facebook.

I never imagined in my wildest dreams that I would find myself smack dab in the middle of the Tibetan plateau, a lone female in a pack of men, doing geologic field research in the ultimate playground of continental tectonic studies. I came to science late in my educational life, having always aspired to be a writer but finding myself pulled toward the allure of a career involving adventures to far off places. It happened my freshman year, in an introductory geology course, one I was taking because I HAD to, not because of an interest in science. I did not consider myself scientifically inclined, had a fear of mathematics, and had never had an Earth science class in my life. But sitting in the back row of that lecture hall, watching the images of such natural wonders as the Grand Canyon, Half Dome, and Mt. Everest flicker across the screen, my curiosity was piqued. Maybe there is something else out there, beyond my comfort zone, that is worth checking out? Geology was like the bad boy in biker boots and I was helpless against its attraction.

Doing geology in Tibet requires hauling all of your gear in a huge truck called a Dong Feng. That is Mount Kailas in the background. How could you not be drawn to this? (Photo by Paul Kapp).

Six years, one bachelors degree, one masters degree, and a move across the country later, I found myself faced with the opportunity of a lifetime. I had just started my PhD work at UCLA and my advisor had some rock samples collecting dust in a drawer in his office. He had grabbed them six years earlier (probably about the time I was sitting in that lecture hall), with the intent of taking a closer look at the geology of the Nyainqentanglha mountain range in southern Tibet. The range had been mapped to first order, mostly as geologists passed by it heading north on the Lhasa-Golmud highway. The highway runs along the length of the adjacent Yangbajing graben, finally hanging a left and heading up and over the range near its northeastern end.

Plenty of geologists had gotten out of their vehicles and poked around in the float while traveling that road toward Nam Co lake and beyond. The range, bounded on its southeastern edge by a large detachment fault, looks like a classic core complex, and lines up laterally with plenty of magmatic rocks related to arc magmatism that was happening during the closure of the Tethys ocean basin. But the rock samples in the drawer were collected from deeper in the heart of the range, valleys had been explored on foot, and these rocks, collected in situ from the valley walls, were the treasures that lay waiting to reveal the secrets of this system; secrets that whispered hints of a more complex story.

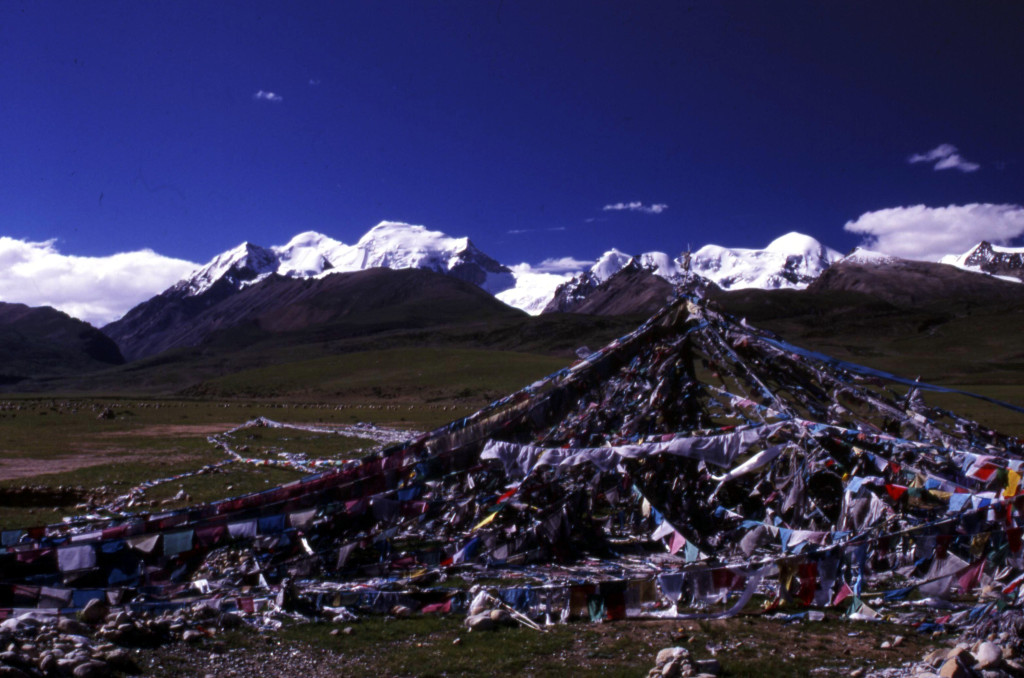

Prayer flags in valley of the Yangbajing graben, southern Tibet. The snow-capped peaks in the Nyainqentanglha range reach over 6,000 meters elevation.

I had started doing U-Pb geochronological studies on zircons as a masters student at Vanderbilt University. I quickly learned that these little accessory minerals are anything but simple – they often contain information from multiple phases of magmatic and/or metamorphic crystal growth, and harvesting that information is a task to be treated with great care. At UCLA, we did this using a High Resolution Ion Microprobe, focusing a small (20 or so micron diameter) beam of oxygen onto the surface of a single crystal, one we had imaged using backscattered electron and cathodoluminescence techniques. Using the images as maps, we could then extract and collect the isotopic information contained in a small area of grain. The imaging helped us navigate the various zones within a crystal, allowing us to maximize the age information garnered from that crystal and avoid getting mixed ages.

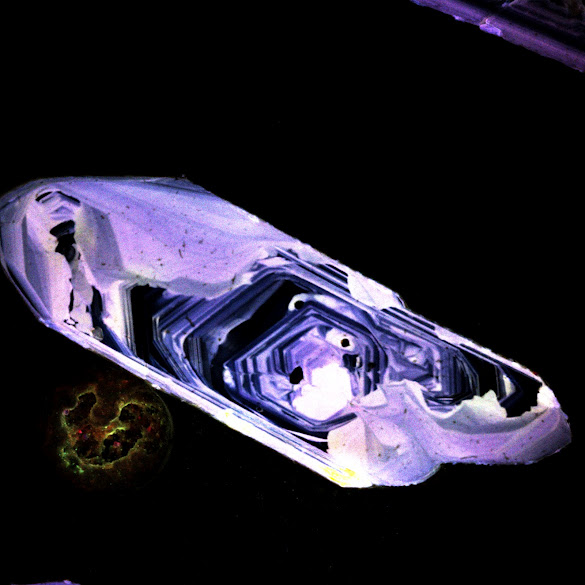

An example of a zircon grain with complex zoning and possible overgrowth. For a crystal like this, we would target the core, the concentric growth zones, and the gray area that appears to be later overgrowth near the rim.

The entire Nyainqentanglha mountain range had been mapped as 60-120 Ma. That is when arc magmatism was going strong in the area, and some of the rocks from the drawer yielded ages that fell within this range. But some were as old as 200 million years and others as young as 8 million years. Eight million years ago happens to correspond to the age of extension for many of the south Tibetan rifts, and we realized there was more to be discovered in these mountains.

And so, it was proposed that I go to the Nyainqentanglha range and dig even deeper into her secrets. As much as I recognized the opportunity before me, I was utterly terrified. I was not an outdoorsy gal. I had done some field work in Nevada, but it was always a week at a time, in designated campgrounds with bathrooms, showers, and food purchased at a local Vons grocery store. This was going to be 100+ days, at high altitude, the only woman in a group of men, 7,000 miles from home and the comfort of my everyday life, cut off from contact with the outside world (This was in 1999, and our only way to communicate was via hard line phone in Lhasa, internet cafe email in Lhasa, or unreliable satellite phone). I wasn’t sure I could do it. My advisor was pretty sure, but my co-advisor was not sure at all. “Even big, strong guys get sick in Tibet. If you get sick, they will send you back to Lhasa on a bus.” In other words, I don’t think you should go, but if you do, don’t slow the men down. It wasn’t exactly a vote of confidence.

Looking back, I realize that there were valid concerns to be had. I did not have experience in the field that proved I could cut it. Hell, I sliced my thumb open on a Swiss Army knife the first time I tried to open one. I didn’t even own a tent, or a pair of hiking boots. But this was my project, I was invested, and despite my fear, my self-doubt, and my unspoken wish that I could just do my project from the comfort of the Ion Probe lab, I knew that going to Tibet would be the single most important experience of my life.

So I went. I bought boots and a backpack. I loaded up a monster size duffle bag with baby wipes, power bars, and plenty of fleece outerwear, and headed off to high altitude adventure with two of my fellow graduate students, Paul Kapp and Mike Taylor. It wasn’t easy. I had never been at high altitude. Meeting with colleagues in Beijing I was told, “Tibet is difficult and you will be defeated.” One man told me he would never allow his wife to go to Tibet, that it is no place for women. We would be hiking 15-20 miles a day, at an average elevation of 15,000 feet, on minimal food, camping days away from human civilization, relying on boiling water from local rivers for drinking, carrying all of our possessions, food, gear, and gasoline in the back of a huge truck – yeah, it was going to be hard core.

And it was hard core.

Camping at the southwestern end of the Nyainqentanglha range. We often woke to frozen boots in our tent vestibules, and a half-collapsed cook tent. The large truck behind the tent is our Dong Feng, which carried all of our food, gear, and gasoline.

It was bizarre.

Me and Mike Taylor crouching inside a small shelter made of yak dung in the Goring La valley, Nyainqentanglha range, Tibet. This was taken two days into a five day trek into the heart of the mountains, yaks carrying our gear.

It was way out of my comfort zone.

Me, inside of our cook tent, holding a side of yak. Our drivers carried this thing around in the Dong Feng for two months, peeling pieces of yak jerky off of it for snacking, or adding to our evening meals. I tried so many new and sometimes unappetizing things on that trip, including yak, goat, yak butter tea, and army-issue canned meat.

And it was amazing, and beautiful, and difficult, and exhausting, and exhilarating, and the single most important experience of my life. It changed who I am. It taught me that I am strong, I am capable, and I am not going to slow anyone down. I spent over 100 days in one of the most remote, wild, harsh places on the planet and I survived. I thrived.

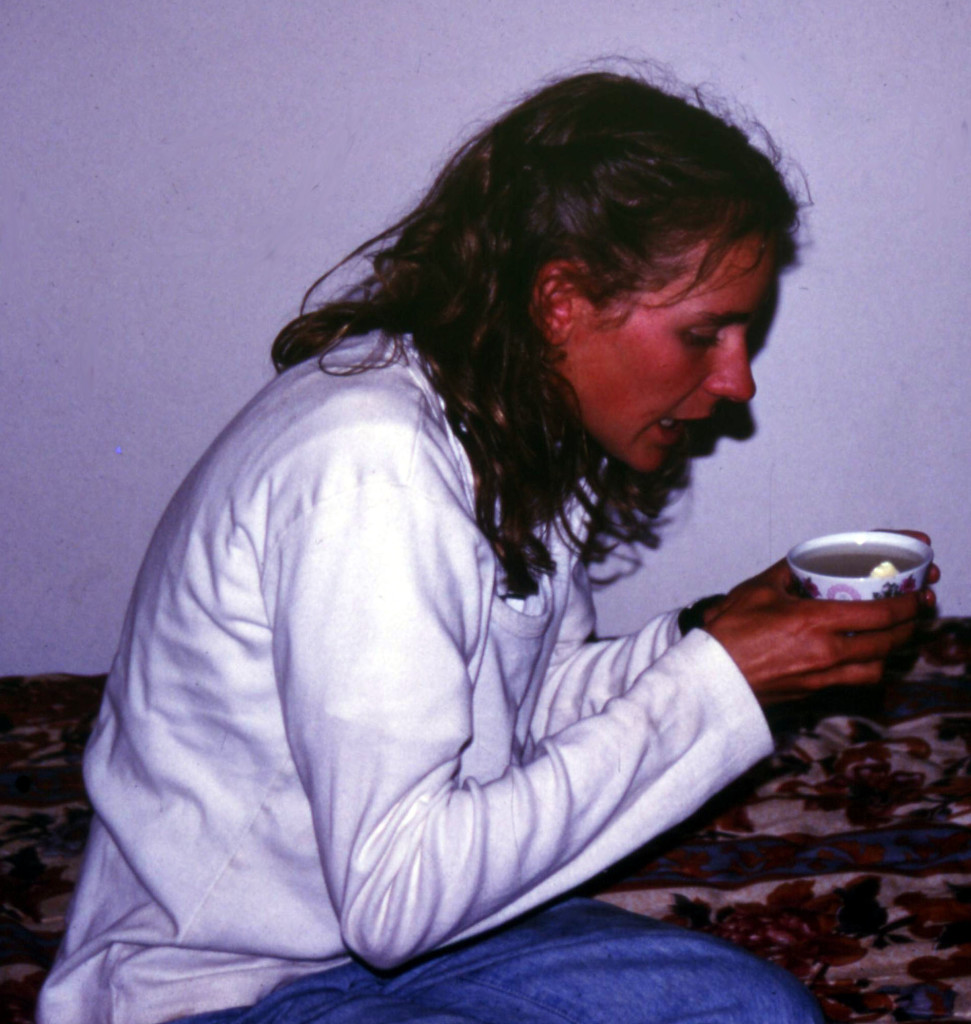

After 100+ days in the field, I was dirty, sunburned, and skinny as hell. But I celebrated a successful field season with a swig of barley wine and the best shower of my life in the Yak hotel in Lhasa.

I learned a little geology along the way. But most of all, I learned that I should never let anyone convince me that something is too hard. I decide if I will be defeated.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.