Kate is a lecturer in Geology at the Camborne School of Mines, University of Exeter. She is interested in applying both organic and inorganic proxies, (such as TEX86, compound-specific techniques, and stable isotopes) to various paleoclimate conundrums from the Cretaceous to the Pliocene. She has sailed twice with IODP, so is now officially a salty old sea-dog. She loves mud, foraminifera, and international geologising. You can follow her on Twitter @Kate_Littler and read more about her research here.

In late November 2014, I packed all the chocolate and shampoo I could carry and flew to steamy Singapore to join up with International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 353, the iMonsoon cruise. Over the next two months our international crew of earth scientists, drillers and sailors would probe the deep ocean floor of the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea, using the specialist drill-ship the JOIDES Resolution (the “JR”), to unlock the mysteries of the ancient Indian Monsoon.

Thankfully the wonderful Rehemat Bhatia has already done a cracking job of describing what IODP is and how a typical expedition is run, so I will concentrate on describing to you both the motivation for the cruise and some of the adventures that befell us during our 56 days at sea. If you’re interested, you can learn more from the blog that I kept while at sea.

Why should anyone care about the ancient Indian Monsoon?

The SW Indian Monsoon drenches India every summer, bringing about 85% of the region’s annual rainfall in only a few short months. This intensely seasonal deluge provides agricultural freshwater for over a billion people, but its strength varies from year to year; sometimes triggering drought conditions and sometimes bringing damaging floods. It is therefore very important from a societal point of view to try to understand how the Indian Monsoon will change in character in the coming decades, as the Earth responds to rapidly increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and the inevitable warming this will bring.

Although there is much variation in monsoon strength on interannual timescales, linked to global phenomena such as ENSO, there are also trends in monsoon behaviour on much longer timescales that stretch far beyond instrumental records into Earth’s deep past. For example, we know there was variability in monsoon behaviour controlled by orbital cyclicity on the thousand-year timescale, and even million-year variability likely linked to the uplift of the Himalaya-Tibetan Plateau and changing oceanic gateways. We would especially like to know how the monsoons behaved during past periods of high atmospheric CO2, like the mid Pliocene, to try and use the lessons of the past to inform our near future policy decisions.

In order to understand this long-term evolution we need continuous high-fidelity records of the Indian Monsoon, extending back many millions of years. The sediments from below the seafloor around the Indian subcontinent are the perfect place to find such records, but prior to IODP Expedition 353 they had never been scientifically drilled before.

Why does the deep ocean around India provide such good monsoon records?

You can think of the oceans as gigantic bowls, into which all the rock and mud that has been eroded from the land will eventually collect, washed in by rivers the world over. Around the Indian subcontinent this outflow is dominated by monsoon-fed rivers, like the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Mahanadi. Over time this monsoonally-sourced mud collects in layers at the bottom of the oceanic bowls, recording the history of all the rock that has been eroded from the land over the millennia. Mixed in with this mud are organisms that live in the water or sediment within the bowl, from tiny microscopic plankton to the great whales. These too will eventually settle into the depths of the ocean bowl upon death, to be incorporated in the great muddy ticker-tape of time.

Using sophisticated sedimentological (mud), paleontological (creatures), and geochemical (chemistry), techniques we can reconstruct key physical parameters such as temperature, salinity, water column stratification, and sedimentation rate, which we can then link back to monsoonal variability. Some of this work is done back in our labs on dry land, and some is done while still at sea during the expedition.

Trials and tribulations on the high seas

On day one we were hit by lightning.

Not that anyone really noticed, until the time came to start lowering the pipe at our first drill site, 285 nautical miles from the nearest land, and we realised the hydraulics in the derrick were fried. Ah the joys of working at sea! But no matter, a mere 6 hours later our crack team of roughnecks (the affectionate nickname for the expert drilling crew who bring us the precious cores) had fixed the problem and we were lowering (“tripping”) pipe down through the 2900 m of water that overlies the seabed here. A testament to the skills and determination of the experienced IODP crew – nothing fazes them.

The 61 m-tall derrick, used to support and lower the drilling pipe, is a surprisingly good lightening conductor…

On board the JR this time we had a 122-strong crew, including 30 scientists representing 10 different countries (Japan, Korea, USA, UK, Germany, France, Australia, Italy, China, and Sweden), along with a dedicated team of sailors and roughnecks of various nationalities including the Philippines. Over the next two months, working 12 hour shifts (with no days off), we would go on to successfully core six sites in total – one on the 90E ridge off NW Indonesia, one in the west-central Bay of Bengal, two on the NE Indian margin, and two in the Andaman Sea – recovering over 4.2 km of pristine core in total.

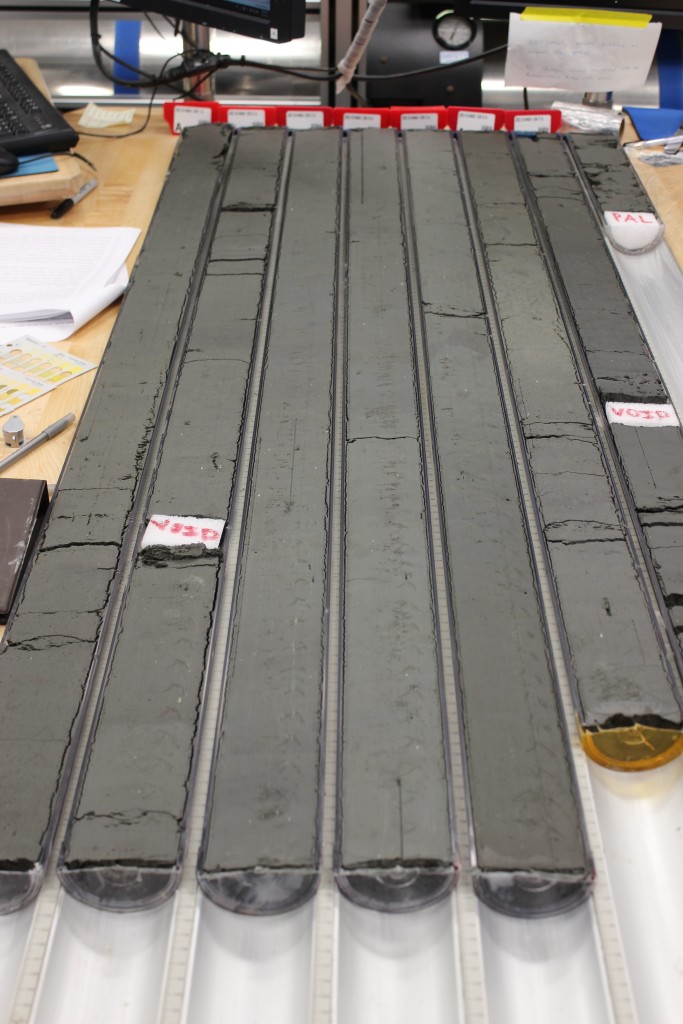

We recovered high-resolution marine records spanning the Pleistocene from all six sites, and Pliocene to Miocene sediments from five of the sites. One of our sites even has a continuous record of sedimentation all the way back to the late Cretaceous, some 70 million year ago. All the scientists, each according to our scientific speciality (palaeontology, palaeomagnetism, sedimentology, physical properties etc.), examined the cores to tease out the information buried within. As a sedimentologist, my job was to help describe the cores in terms of colour and composition, aided by the examination of over 1000 smear slides using a light microscope. Spending 12 hours a day on a microscope will sure make you appreciate weekends as well as subsidised eye tests back home…

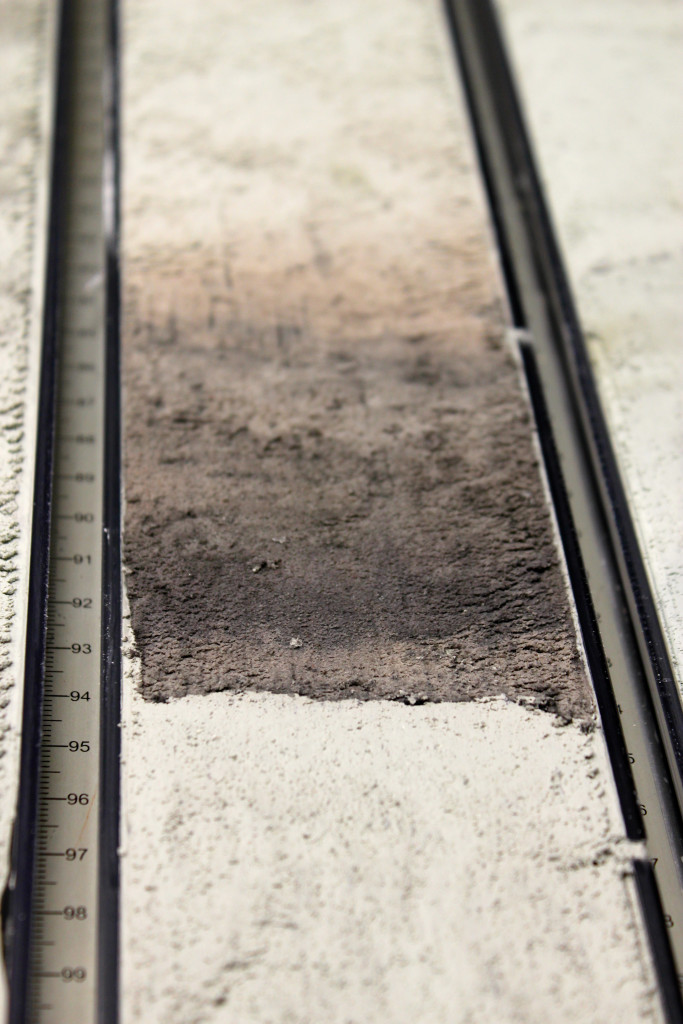

In addition to the beautiful deep-sea muds, we discovered volcanic ashes laid down by violent volcanic eruptions in Indonesia thousands of years ago. These included the huge Toba eruption about 70,000 years ago, (rated “apocalyptic” on the volcanic explosivity index), which has left a blanket of ash up to 25 cm thick all across the northern Indian Ocean and which may have caused a bottleneck in human evolution.

The initial scientific results of IODP Expedition 353 are too numerous (and indeed, mostly embargoed until late 2016) to outline in detail here, but overall the expedition was hugely successful. You can see the short preliminary report here if you’re interested.

Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink

While at sea we are totally self-sufficient, making all our drinking water on the go from seawater, and carrying all the fuel and food we need to keep the large team of people going for 56 days straight. Luckily there is a great team of catering and cleaning staff who do a fantastic job of keeping us fed, watered, and comfortable in clean clothes. It truly is a shock to go back home after two months on the “JR Hotel” and have to cook for yourself again!

As our two month expedition straddled Christmas, the effort that the catering crew went to in order to make sure we all had the best possible time was particularly appreciated, even if we were still missing our families.

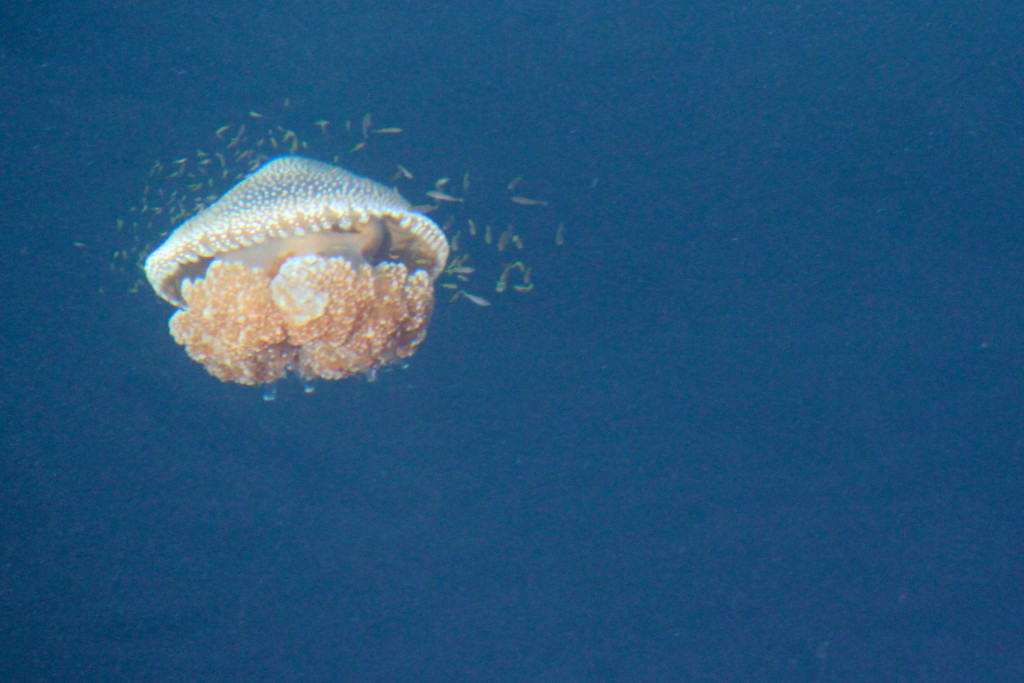

As well as all the hard work toiling away on seemingly endless 12-hour shifts, there is also some time for wildlife spotting, sunset appreciation and some relaxation. For the dayshift (noon–midnight), taking time to appreciated the gorgeous sunset after lunch became something of a daily ritual, as did appreciating the sunrise for our night shift (midnight–noon) counterparts. We even found time to take part in the first “JR International Ping Pong tournament” to the great amusement of all. We also took the time to make sure we hit the onboard gym as often as we could, because sitting at a microscope apparently doesn’t burn off the 4000+ calories a day you end up consuming on the JR…

Working together intensely for two months in close quarters means you get very close to your shipmates, and great friendships are forged along the way. All the scientists look forward to receiving our allocated samples over the coming months and getting to work unravelling the mysteries of the ancient Indian Monsoon. Stay tuned for the exciting scientific results.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.