Lloyd White is currently a Postdoctoral Research Fellow with the Southeast Asia Research Group (SEARG) at Royal Holloway University of London. He was previously based in Australia, where he worked as a Postdoc (funded by the Australia-India Strategic Research Fund) and PhD student at The Australian National University (2008-2012) and as a Research Geoscientist at Geoscience Australia (the Australian national geologic survey) (2006-2008).

I have spent the past two years investigating the geology of Indonesia. This has ranged from hiking up rivers and volcanoes to collect samples along the island of Java, mapping road outcrops and quarries in Sulawesi and using boats and small planes to access remote outcrops in western New Guinea (West Papua). I’ve also been involved in more lab-based studies, for instance trying to use geochronology, geochemistry and mineralogy to find the enigmatic source of Borneo’s diamonds.

While I am a structurally inclined field geologist, most of my work focuses on dating sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic rocks to better understand the broader tectonic evolution of Indonesia and other parts of Southeast Asia. This is important there are relatively few geological studies in Southeast Asia compared to many other regions of the world. This is also quite surprising when you consider that it covers a similar area to North America.

One of the main challenges in working in Southeast Asia is actually finding rocks to study. Much of the region is covered in dense rainforest, so we typically walk up rivers which provide a natural path into the jungle and at the same time cut into, and expose bedrock. In some places we can use a boat to access outcrops along the coast, or we may be fortunate to find newly constructed roads and quarries that expose fresh rocks. However, most roadside outcrops are effectively lost or degraded after a year due to either intense tropical weathering or the rapid growth of jungle vegetation. But, after working in the Himalaya, Australia and Europe I’ve learnt that everywhere has its challenges in accessing rocks (the Himalaya may have nearly 100% exposure, but without a jetpack most exposures are difficult to access).

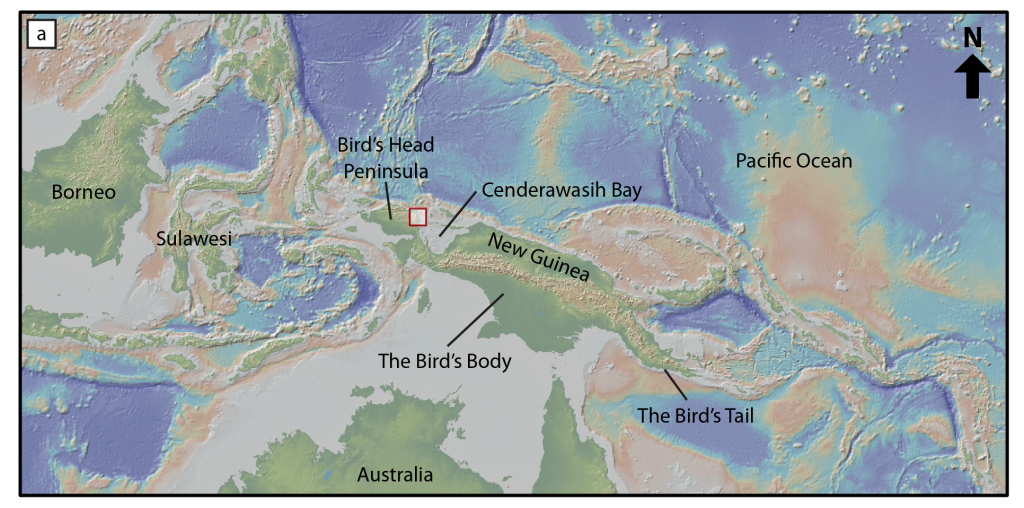

Topographic and bathymetric map of New Guinea, highlighting its bird-like shape. The Bird’s Head is located in the west and is part of Indonesia. Half of the Bird’s Body is within Indonesia, whilst the other half is within Papua New Guinea, along with the Bird’s Tail. Base map obtained using Ryan et al. (2009).

Me and my student Max Webb, hiking from our basecamp in the Netoni Valley into an impending downpour (photo credit: Ben Jost).

Most recently I have been leading a project to re-map and re-date rocks in West Papua on the island of New Guinea. We refer to this area as the “Bird’s Head” [or Kepala (Head) Burung (Bird) in Bahasa Indonesian] because New Guinea is broadly shaped like a large bird, with its head and neck in the west, a central body and its tail in the very east. This is relatively poorly explored as the region is quite mountainous as well as densely forested. It was first studied by Dutch geologists in the 1930’s-60’s, and later with a combined effort of Indonesian and Australian government geologists in the 1970’s and 1980’s, but since this time, very little geological work has been conducted. While the early work was quite detailed, it is limited by the techniques that were available to the geologists in the past. So much of what we know about the timing of tectonic events in New Guinea relies on biostratigraphy and whole-rock K-Ar isotope geochronology often conducted on float samples to ensure the best, unweathered material was dated. It is likely we will obtain a better understanding of the timing of tectonic events by dating samples that were collected in-situ, using modern geochronological methods (e.g. U-Pb and He dating of zircon, and Ar-Ar dating of mica and K-feldspar).

In May 2013 I was fortunate to be invited to do some fieldwork in and around the Bird’s Head and Neck using a large ‘live-aboard’ dive boat called the Shakti. We used the boat as floating hotel and as a launch for speed boats so that we could access remote coastal outcrops. The overall point of this work is to gain a better understanding of the rock types around Cenderawasih Bay. A significant proportion of the bay is reserved as a marine national park, setup to protect rare Whale Sharks and other sea life such as Dugongs. I suspect this wildlife is why we saw Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior III in one of the local ports.

Whilst a lot of the time is spent hiking up rivers in hot, tropical conditions, there are some idyllic places to search for outcrops, particularly here on Mansinam Island in Cenderawasih Bay.

We found recent evidence of faulting around the edge of Cenderawasih Bay, in this case a submerged forest indicates extensional faulting took place not too long ago.

After the successful boat expedition in 2013, I returned to Cenderawasih Bay and the Bird’s Head in September 2014. This time we explored more inland areas of the Bird’s Head with one of my Indonesian colleagues (Dr Indra Gunawan) and two of my graduate students (Ben Jost and Max Webb). I was quite nervous before this trip, as I knew I needed to use some small aircraft to reach particular locations. This was made worse as in the weeks preceding the trip, I had been watching Channel 4’s program “Worst Place to be a Pilot”, a show that focussed on the daily life and dramas of pilots working for Susi Air, an Indonesian airline company that flew light planes to isolated areas of Papua. In the end it all worked out fine, but these is nothing more worrying when flying than seeing the pilot and co-pilot look at one another and both cross their fingers. Although, perhaps they were just concerned about the (crazy?) guy aboard that just purchased a ticket to reserve a seat for his heavy (100 kg) rock laden bags.

Whilst we’ve now visited a considerable number of locations across the Bird’s Head, we still have a lot of ground to cover, and it is clear that we have our work cut out for us. However, we have been fortunate in developing good relationships with several biologists working in the region, including botanists from Universitas Papua (UNIPA) and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew as well as a beetle specialist from Germany. Our collaboration can be as simple as sharing GPS tracks and photos after field seasons so that we all have a better understanding of the conditions in particular regions and the location of roads (sorry, I forgot to mention that there is no reliable street directory for this part of the world, although Google Earth imagery has been quite useful for spotting the location of navigable tracks). We are hoping that such collaborations will continue to grow and that our geological work will not only be of interest to geologists, but might also benefit the biologists working in the region. For instance, new maps showing which rocks developed as part of Gondwana/Australia vs. in the Pacific, might shed new light on the evolution and extent of particular plants, insects and animals. The challenge now is to lock myself in the lab to examine the rocks that we’ve collected so far.

![We are fortunate to work with a number collaborates across Indonesia. This is our field team from September 2014 with Dr. Indra Gunawan (Institut Teknologi Bandung [ITB]), Pak Jumiko Sarira (Universitas Negeri Papua [UNIPA]), Ben Jost, Max Webb and I (Royal Holloway University of London) along with our friendly drivers and porters.](http://www.travelinggeologist.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Fig9-Group-Picture-Kebar-Valley-1024x658.jpg)

We are fortunate to work with a number collaborates across Indonesia. This is our field team from September 2014 with Dr. Indra Gunawan (Institut Teknologi Bandung [ITB]), Pak Jumiko Sarira (Universitas Negeri Papua [UNIPA]), Ben Jost, Max Webb and I (Royal Holloway University of London) along with our friendly drivers and porters.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.