Ria is a Postdoctoral Research Assistant at the Natural History Museum in London who uses new physical and chemical analytical methods to characterize modern-day primitive soils and mineral substrates associated with cryptogamic ground covers – You can read more about here research here.

To me, as a geologist, planning fieldwork in Iceland couldn’t have been more exciting. It’s one of those case studies that appears in every geology/geography/earth science text book in the world, primarily because the Mid-Atlantic Ridge emerges above sea level onto land and the island being incredibly tectonic and volcanically active. Iceland is one of the most volcanically active countries in the world, delivering a near continuous emergence and formation of new, volcanic land surfaces and islands. As such, it’s the perfect location to study numerous geological and environmental processes on a short (in geological terms) timescale.

Our reasons for fieldwork were not so much focussed on these impressive and extensive volcanics, but rather their weathering products. We are primarily investigating the colonisation of modern volcanic environments (be they rocks, soils, loose substrates) by cryptogamic organisms (non-vascular plants (e.g. bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, hornworts)), lichens, biological soil and rock crusts), organisms that are directly descended from those that formed the first complex terrestrial ecosystems in the Early Palaeozoic. We are studying how these organisms and their respective symbionts (e.g. fungi) contribute towards weathering and eventual soil formation at the modern day, with a view to applying this to direct comparisons between early fossil microsoils and their modern analogues.

Iceland is cryptogam-rich, largely untouched by human ‘contamination’, and fairly lacking in higher vascular plants which tend to out-compete small herbaceous plants such as the bryophytes in more established floral habitats in other parts of the world. In essence, Iceland ticks all the boxes.

So, in September 2014 a geologist (myself), a palaeobotanist (Prof. Paul Kenrick) and a bryologist (Dr Silvia Pressel) left for fieldwork on a day where Iceland was apparently experiencing its ‘worst’ storm of the entire summer. After a particularly terrifying landing (in which we later found out the flight from Glasgow ahead of us had to abort mid-descent), we subsequently abandoned the day’s fieldwork and navigated our way along the coast to our first base in Reykjavik; this proved challenging as we battled horizontal rain, low cloud cover and gale force winds, whilst trying not to veer off the road and into the sea. However we did survive to tell the tale, and upon waking up the next morning we realised why Iceland has the reputation of being the fascinating and geologically-stunning country that it is.

We stayed in numerous locations covering as much of the country as possible: Reykjavik in the south-west (this particular apartment had a life-size plastic horse in the living room… Wondering about its purpose, we later realised it was in fact a lamp. Why wouldn’t it be?!), Grundarfjörður on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula in the north-west, and Akureyri (the ‘Capital of the North’). Over the course of the week we: studied the geothermal areas of Geysir and Hveragerði, noting how remarkably proximal bryophytes grow in relation to geothermal vent openings (soil temperatures here reaching up to 80°C); navigated the moraine slopes of the Sólheimajökull glacier… Bryophytes, particularly thallose liverworts, colonising even the most unstable of coarse volcaniclastic substrates; trekked numerous lava fields ranging from 40 to 1,000 years of age (including the Krafla Fires and Mývatn Fires), which indicate varying degrees of weathering and colonisation, mostly dependant on age and mineralogy; glacial fluvial outwash systems originating from the volcano made famous by Jules Verne, Snæfellsjökull, the sedimentary banks of which are covered with massive and extensive cryptogamic carpets which in effect act as a stabilising and consolidating agent; gazed into a crater lake in the Krafla caldera (the wind was so strong Paul’s glasses blew right off his face and he didn’t realise); wondered across the rift valley of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at Þingvellir, stopping to study the widespread cryptogamic covers surrounding Lake Mývatn; and finally marvelled at the large cinder cone at Hverfjall, whose slopes provide the volcaniclastic substrate to widespread cryptogamic mats and covers at the base; as well as everything else in between. We covered a total distance of ~1300 miles in a hire car affectionately named ‘Lionel’ (after one Mr Ritchie, whose song ‘Hello’ became the theme song of the trip). We even saw the sun on a few rare occasions, which afforded fantastic views of the recently erupting Eyjafjallajökull, Kleifarvatn lake, and Vestmannaeyjar (the Westman Islands, including the ‘geologically new’ Surtsey and Heimaey).

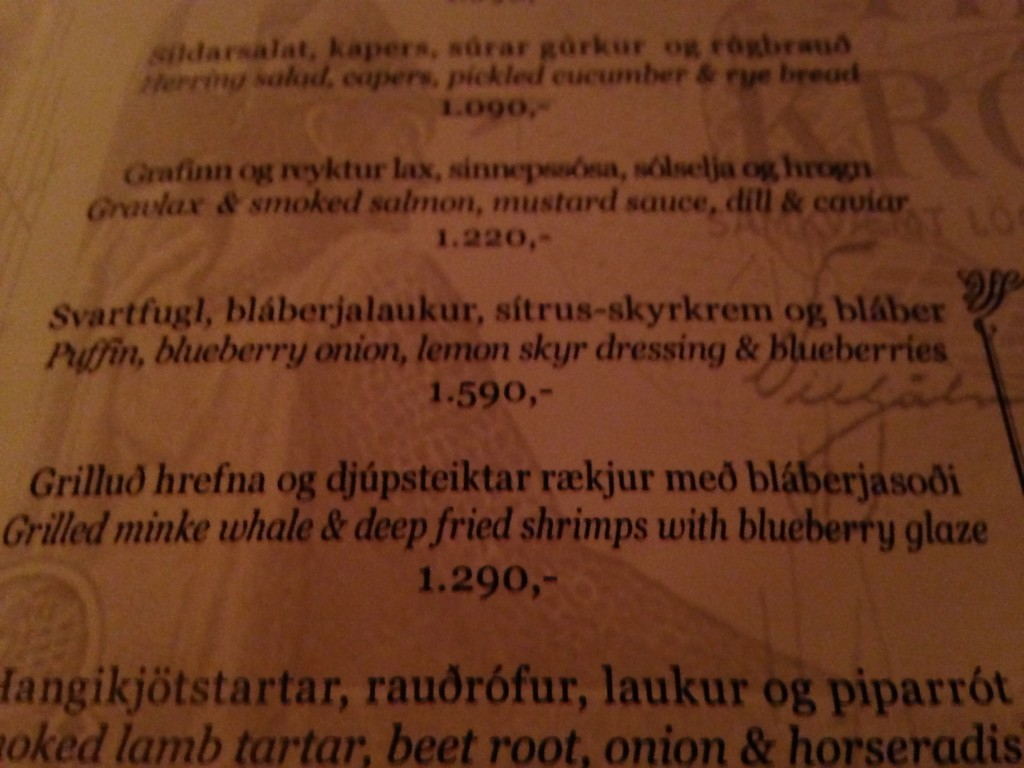

None of us were brave enough to try the local delicacies of minky whale, puffin or shark (I did however have a lobster hotdog), but the hospitality was fabulous. By the end of it we were reluctant to leave. I don’t think I’ve said ‘oooooh’ and ‘aaaahhhh’ so much in my life!

Extensive mixed cryptogamic communities on slump slopes near to the summit of Krafla (note pipeline from a geothermal power plant below us).

Snowy afternoon at Namafjall hot springs. Apart from the temperature, it was hard to tell what was geothermal steam and what was blizzard.

Kleifarvatn lake on the Reykjanes Peninsula. Cryptogamic communities thriving on loose ground on the lake margin.

Kleifarvatn lake on the Reykjanes Peninsula. Cryptogamic communities thriving on loose ground on the lake margin

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.