by Kellen Gunderson

The 19th century industrial revolution was powered by coal. In the United States most of that coal came from a region in Northeastern Pennsylvania called the anthracite coal belt. Coal was first discovered there in the late 18th century and commercial coal mining began in the early 19th century with the formation of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company. By the end of the American Civil War, the coal industry was booming in the U.S. The coal regions were crisscrossed by railroads and canals that took the coal from the mines to the industrial centers of Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore. The regions were filled with small towns of immigrants that came from faraway places such as Ireland, Germany, Poland, Italy, Lithuania, or Wales to work in the mines. Immigrants from one country would often flock to the same town so that it was not uncommon to hear Polish spoken in one town and Italian in the next town over. The effects of this multi-ethnic influence can still be observed in the region today.

By the mid 19th century the mining boom began to die down in Pennsylvania. But modern geologists still benefit from the now defunct industry because the extraction of all that coal created some world class exposures of the geology that were previously hidden from view.

|

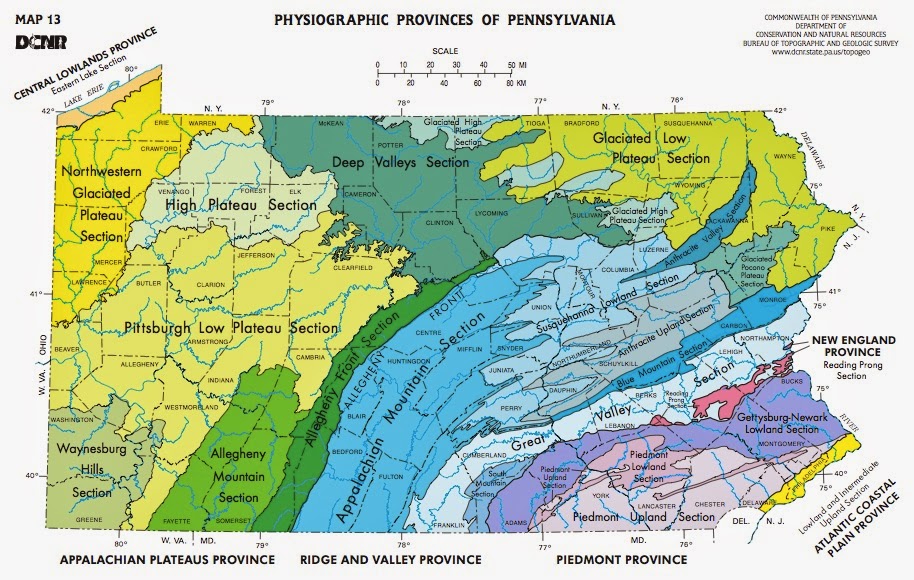

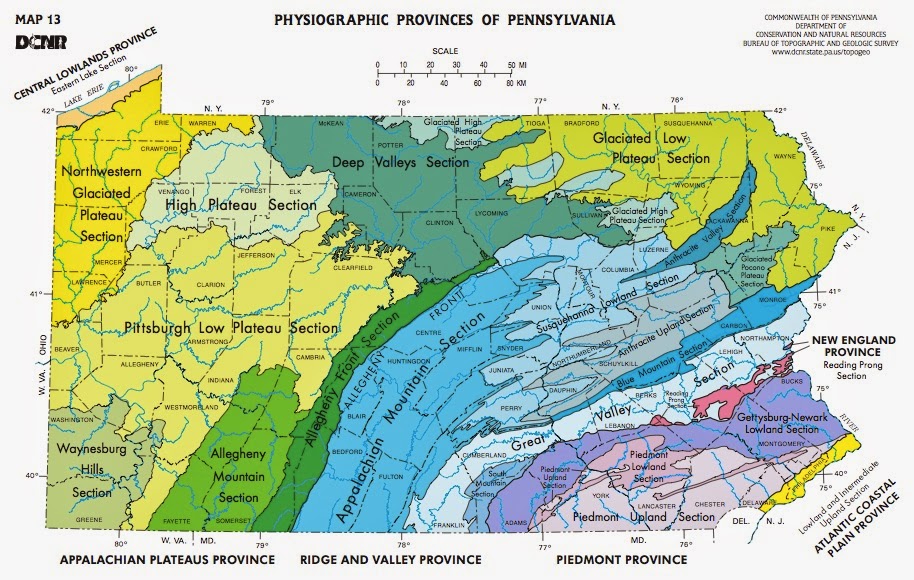

| Physiographic map of Pennsylvania showing the locations of the anthracite producing provinces in Northeastern Pennsylvania. |

Any student who has taken a structural geology class while studying at a university in the Mid-Atlantic United States is undoubtedly familiar with the outcrop at Bear Valley strip mine. The Bear Valley mine is located in Shamokin, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. Bear Valley exposes a series of tight folds in the Pennsylvanian (Upper Carboniferous) Llewellyn Formation. The mine is an excellent place to teach students the basics of measuring and mapping geologic structures. It also is a great place for fossil hunting. It is essentially impossible not to find numerous fossil leaves and ferns or even the occasional intact 300 million year old tree trunk.

|

|

The “whaleback” anticline (center view) plunges out below the syncline exposed on the quarry wall. Often this is the first place students learn to visualize structures in three dimensions.

|

Large fossil fronds in the Llewellyn Formation on the quarry wall at Bear Valley. Fossil hunting is so easy here that even a structural geologist can come home with a good haul.

|

| Numerous small-scale secondary structures are also visible at Bear Valley, including these conjugate normal faults that accommodate extension on the hinge of the whaleback anticline. Well developed slickenlines indicate the direction of fault movement. |

Not far from Bear Valley is the infamous ghost town of Centralia. It is the site of a coal mine fire that began in 1962 and still continues today. The coal caught on fire after being accidentally ignited by the townspeople who were burning trash in the municipal landfill. Over the next several years, the town was evacuated due to the noxious fumes coming from the ground and the sudden appearance of sinkholes as the fire burned through the underground coal seam.

Today Centralia is a ghost town. Many of the streets are still there, along with a few abandoned public buildings but everything else has been demolished. Smoke still rises from the ground and it is estimated that the underground fire has enough fuel to burn for hundreds of years more.

|

| Smoke rising from the former site of the Centralia landfill. There is a fear that the fire might follow the coal seam all the way over to the other limb of the anticline and threaten the town on the other side of the mountain. Who knows how long it will take to burn its way over there? |

|

| The Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church in Centralia is a testament to the hard-working immigrant people who populated the region and worked the mines. |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.