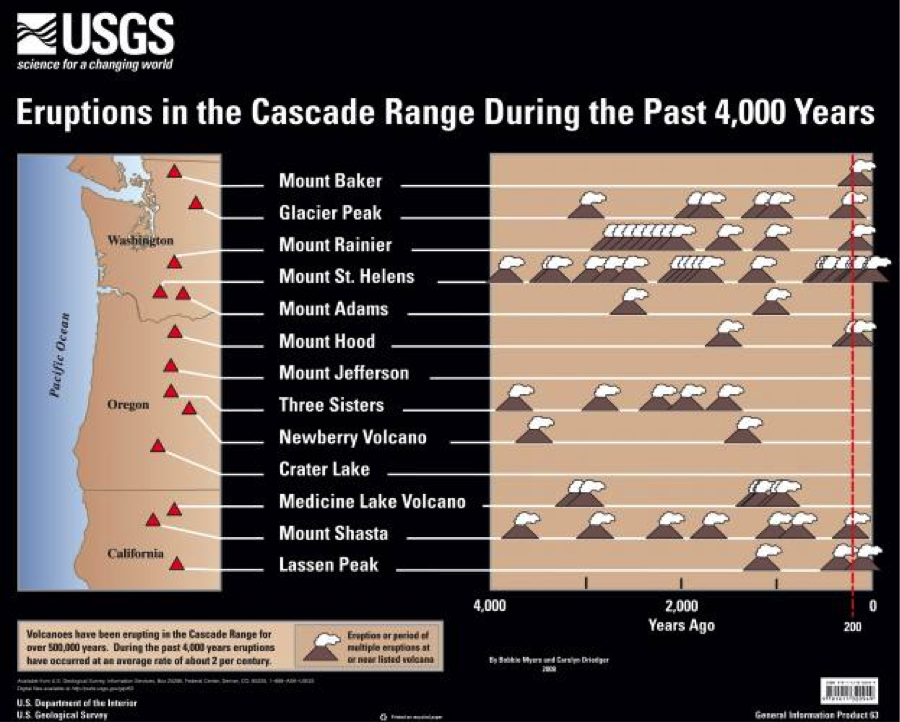

The rugged and heavily glaciated Cascade Range stretches from northern California through Oregon, Washington and into southern British Columbia. The Cascades are the result of millions of years of collisions, uplift, and volcanic activity. Lassen Peak and Mt. St. Helens were the only volcanoes to erupt during the 20th century with major eruptions in 1915 and 1980, respectively. Both eruptions produced immense ash columns, devastating pyroclastic density currents and lahars (volcanic mudflows). Fortunately both eruptions took place far from any major population centers. There are other volcanoes in the range however, that pose a major threat to the ever-growing population of the Pacific Northwest; namely, Mt. Rainier.

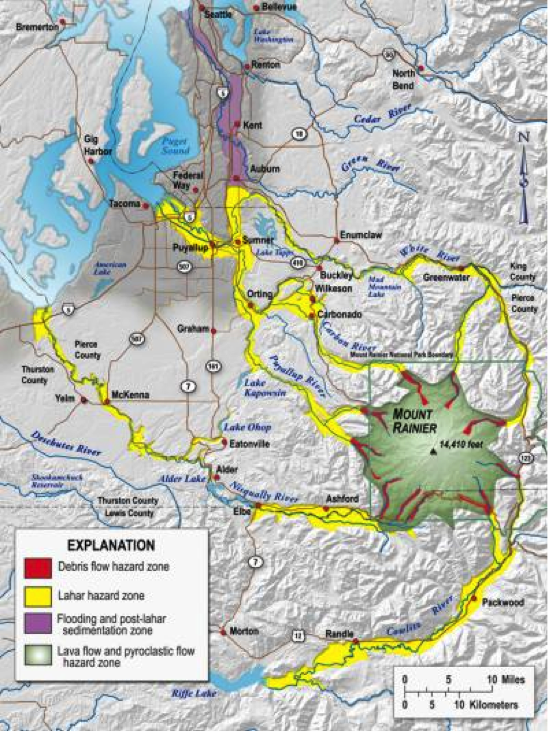

Mt. Rainier is not only the highest mountain in the Cascade Range and the most prominent and most glaciated peak in the contiguous United States, but is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. This isn’t because Mt. Rainier will necessarily produce a larger eruption than other volcanoes, but because of its proximity to a densely populated area. Previous eruptions left lahar deposits in the Puget Sound lowlands near Tacoma and spread tephra (ash and pumice) over much of Washington State.

I have spent a lot of time on and around Mt. Rainier for various outdoor pursuits – hiking, climbing, skiing, and exploring. In all I’ve been to the summit three times, I’ve been on numerous routes on the upper mountain, and I’ve hiked all the way around volcano via the Wonderland Trail. My experiences on Mt. Rainier have exposed me to a number of mountaineering-related hazards and volcano hazards. As a climber, hazards like rock fall, avalanches, storms, and crevasses exist and can be mitigated with experience, caution, and thorough trip planning. However, the hazards are always there. In addition to these hazards, the volcano presents other hazards that can occur with or without an eruption.

|

||

|

Climber’s make their way up Mt. Rainier with a backdrop of the Tatoosh Mountains and Mt. Adams

|

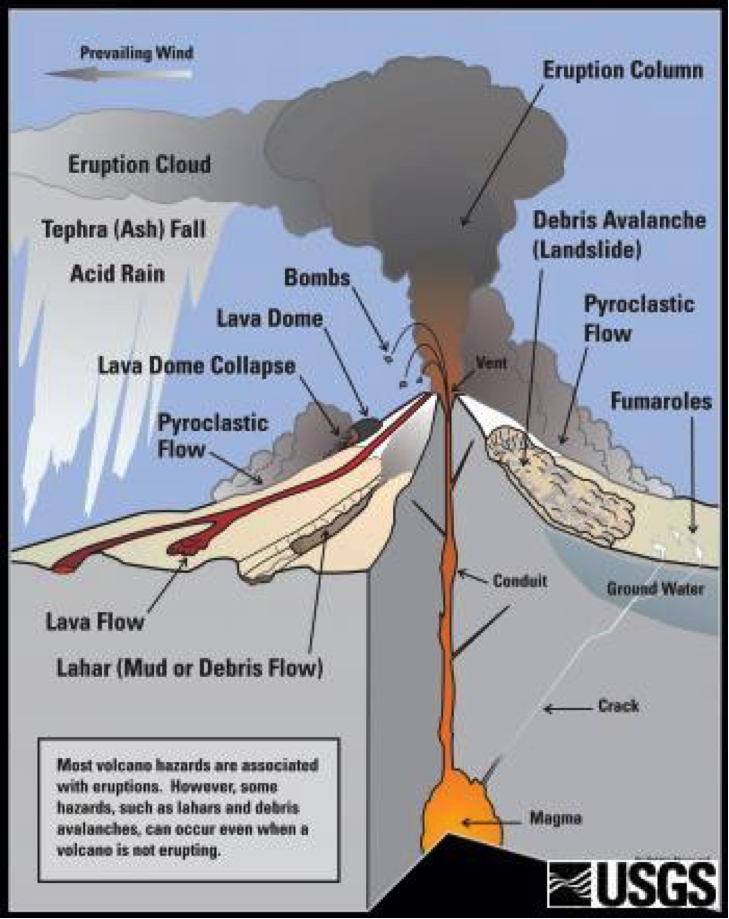

The volcano has a long and complex history of growth and erosion. Thunderous rockslides and avalanches, glaciers slowly carving the mountain and bulldozing rock downhill, mud- and silt-saturated glacial streams, and hot, sulfur-rich fumaroles spewing from the summit crater were a few of the geologic processes I witnessed while on the mountain.Putting the geologic history of any volcano in the correct sequence can be complicated.Many of the rocks at Mt. Rainier are visibly hydrothermally altered, or chemically weakened by hot groundwater.As a result, landslides have played a major role in the shape and geomorphology of the volcano and the deposits downstream.In fact, much of the northern and western flanks of the mountain slid away in catastrophic landslides, which transitioned to dense mudflows that traveled up to 70 miles away from the volcano in previous centuries.Many of the suburbs of Tacoma and Seattle sit atop these old mudflow deposits.Landslides and mudflows are amongst the most dangerous hazards associated with Mt. Rainier because they can occur without an eruption and offer no warning to scientists that constantly monitor the volcano for signs of unrest.

In general, most volcano hazards are related to eruptions and usually offer good warning signs. Prior to an eruption, magma must rise from depth into the volcano. The magma, which is under pressure, breaks the rock and creates small earthquakes that are recorded by seismometers. Additionally, high-precision GPS and tiltmeters can be used to track changes in the size, shape, and slope of the volcano when magma causes the volcano to swell. Additionally, the rising magma will degas large amounts of SO2, CO2, and H2O, which when monitored regularly, can indicate changing conditions and shallow magma. If a major eruption were to occur, it would likely start showing signs of unrest days, weeks, often months in advance.

|

|

Gibraltar Rock is a ridge composed of altered lava and pyroclastic surge deposits

|

|

|

The quiet giant at Reflection Lakes

|

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.