This is part 2 of 3. You can read part 1 here.

Probably the best field trip* in the world ever!

(*and it wasn’t even a field trip)

Part 2 of 3: Los Angeles to Yosemite

It was two years ago that we agreed to have an extra-special family summer holiday. Deciding on a road trip across part of America, my family came up with a list of places to visit: Las Vegas, Palm Springs, Los Angeles, San Francisco … All I had to do was come up with the itinerary. Some surfing around the region via Google Earth showed that it would be possible to link the above cities with some very interesting geological localities indeed, traversing parts of the relatively stable Colorado Plateau, the more heavily-deformed “Basin and Range” Province, as well as the tectonic crush zone that is the Californian Pacific Coast.

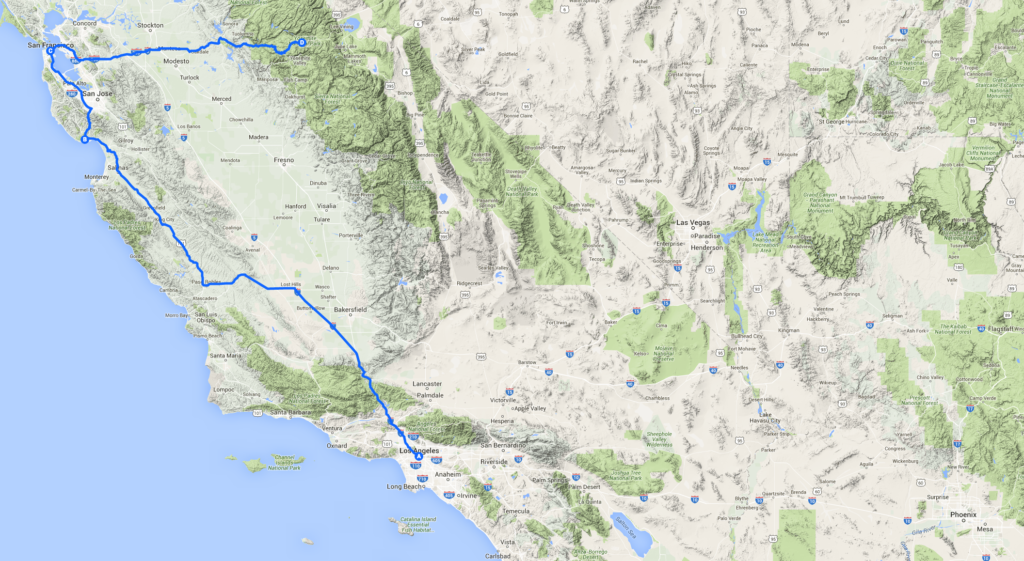

The first leg of the ensuing road trip, from Las Vegas to the Grand Canyon and then Palm Springs and Los Angeles, I described in the first instalment. This second piece covers the section from Los Angeles, up the Pacific Coast to San Francisco, and then inland to Yosemite.

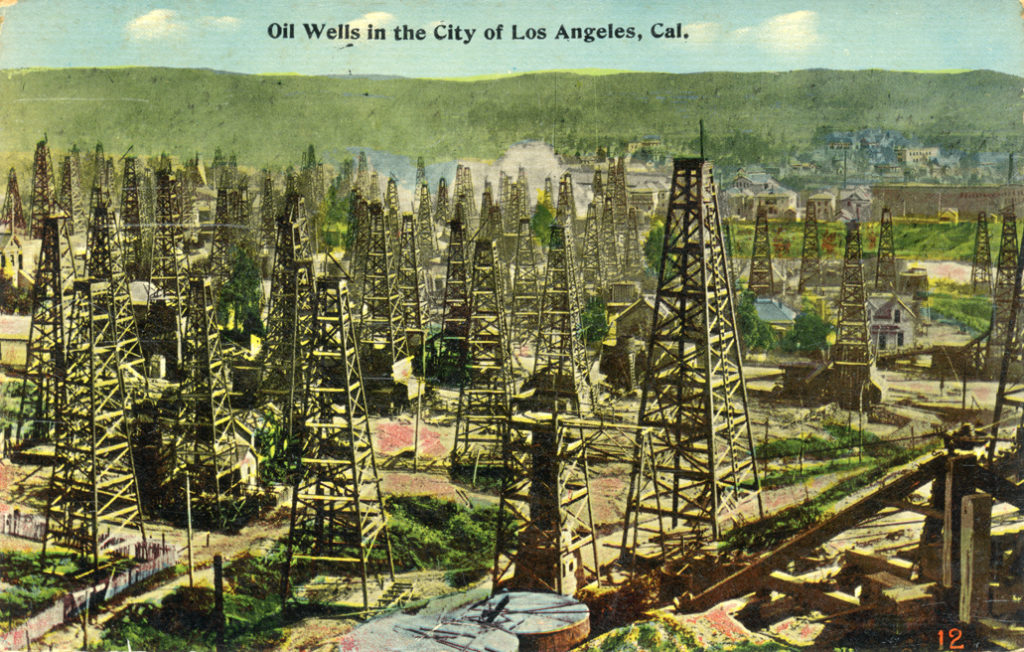

Arriving in Los Angeles, we had a couple of days in which the geology took a back-seat. The famous “La Brea” tar-pits are surprisingly located only a mile from Beverly Hills and Hollywood, although sadly I never got around to visiting them. But (as a petroleum geologist) I could rest assured with the knowledge that numerous prolific oil fields are located directly beneath the city. In the case of La Brea, it is underlain by the Salt Lake Field, which produced over 50 million barrels of oil between 1902 and abandonment in 2001 to make way for a new shopping mall. The Los Angeles petroleum system developed in deep pull-apart basins controlled by the San Andreas Fault, with oil in Miocene sandstone reservoirs trapped within complex thrust-cored anticlines. There’s surprisingly little to tell these days of the city’s oily heritage, although one obvious exception is a series of oil production platforms clearly visible a short distance offshore of the coast between Santa Monica and Santa Barbara, northwest of Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, a trip along Mulholland Drive (home of many film stars, and location of the eponymous David Lynch movie) afforded spectacular views of the “Hollywood” sign as well as the sprawling urban Los Angeles city-scape. However, a glance in the other direction revealed the fault-scarp immediately north of the urban area of Burbank, clearly a very young and tectonically-active feature. In Los Angeles, the geology is never far away…

After several days in LA, our journey continued north-westwards along California’s famous Route 1, which hugs the Pacific coastline (in some places, quite literally) all the way to San Francisco. This is a surprisingly long journey that took us a full two days, with the road in places a seemingly never-ending succession of scary cliff-top hairpin bends. The scenery is truly world-class, especially along the section known as the “Big Sur” between the sleepy town of Cambria (a hang-out of ageing hippies and alternative life-stylers) and the uber-upmarket resort of Carmel. As for the geology, suffice to say that the rocks along this mountainous coastline are a chaotic series of contorted sediments, volcanics and melanges uplifted as the now-subducted Farallon tectonic plate squeezed its way under the North American Plate, before the right-lateral San Andreas Fault system took hold. These rocks are exposed all the way up the coastline, but are way too complex to comprehend on a tour like this.

North-west of Santa Cruz, where the coastal scenery becomes more subdued and mellow, was one of my more sneaky geological stops. I had read about the Panoche sand-injectite complex, inland of Santa Cruz, but this is located in mountainous off-road territory and to propose a visit here would have incited my family to mutiny. However, I knew of similar sand injectites (basically, the sedimentary equivalent of igneous intrusions – liquefied sands intruded under high pressure into overlying sediments) exposed in cliffs in the Santa Cruz area. Locating them would be tricky, but I knew approximately where they were through a combination of academic publications and Google Earth. So at what I thought was roughly the right place, I feigned the need for a late lunchtime stop to “stretch my legs” and sauntered down a path to the rocky cove below. The sand injection dyke which I found down there was stunning, and is shown in the accompanying photograph.

We spent a couple of days in San Francisco, with obligatory visits to Devil’s Island, the Golden Gate Bridge, Chinatown and the Fishermans Wharf area. Then another long drive, setting out across the new Oakland Bay Bridge. This runs parallel to the old bridge that was damaged by the 1989 earthquake caused by slippage on the San Andreas Fault (it moved again in August 2014, causing an earthquake just two weeks after our trip). We headed eastwards, inland towards the Sierra Nevada Mountains and Yosemite National Park. At first, this seemed like a tedious journey across the flat agricultural plains of California’s Great Central Valley. The valley is pretty much all that remains of a back-arc basin formed as the Farallon Plate subducted under North America. Depending on which route you take over the Central Valley, you might spot oilfield nodding donkeys amongst the orange groves.

Eventually, the road begins a long and winding ascent into the pine-forested foothills of the Sierra Nevada, before reaching Yosemite Valley nestling beneath the mighty Half Dome.

Yosemite defies description, both in terms of the spectacular scenery of immense granitic cliffs, hanging valleys and waterfalls, but also the sheer volume of granite, an observation that applies not just to Yosemite but the Sierra Nevada Mountains in general. Intruded over a long period of time during the Cretaceous, the Sierra Nevada granites are yet another manifestation of the subducting Farallon Plate, with huge volumes of melt rising upwards into and eventually crystallizing within the overlying American Plate. As a British geologist accustomed to believing that the UK’s Cornubian Batholith, with its outcrops of granite poking through at Dartmoor and Bodmin Moor, is a large-scale feature; well the sheer scale of the Sierra Nevada intrusions in comparison is simply mindboggling.

Onwards from Yosemite, the road winds on and on and up and up eastwards towards the Tioga pass, which at 9943 feet elevation marks the watershed across the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Beware – for anyone attempting to travel this route outside of summer, the road is typically shut for six months of the year due to snow drifts, and a detour would involve several hundred miles of extra driving. As one gains elevation towards the pass, the pine forests thin out and the landscape becomes increasingly dominated by huge bare slabs of glacially-scoured sparkly light grey granite.

By comparison with the long, steady drive up the western flanks of the Sierra Nevada, the eastern margin is fault-controlled and the road drops precipitously beyond the Tioga Pass into a series of deep rifted basins. From here, we headed to June Lake, a beautiful and quiet mountain resort. I’ll enthuse about the geology of this area, and that of Death Valley, in the next and final instalment.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.